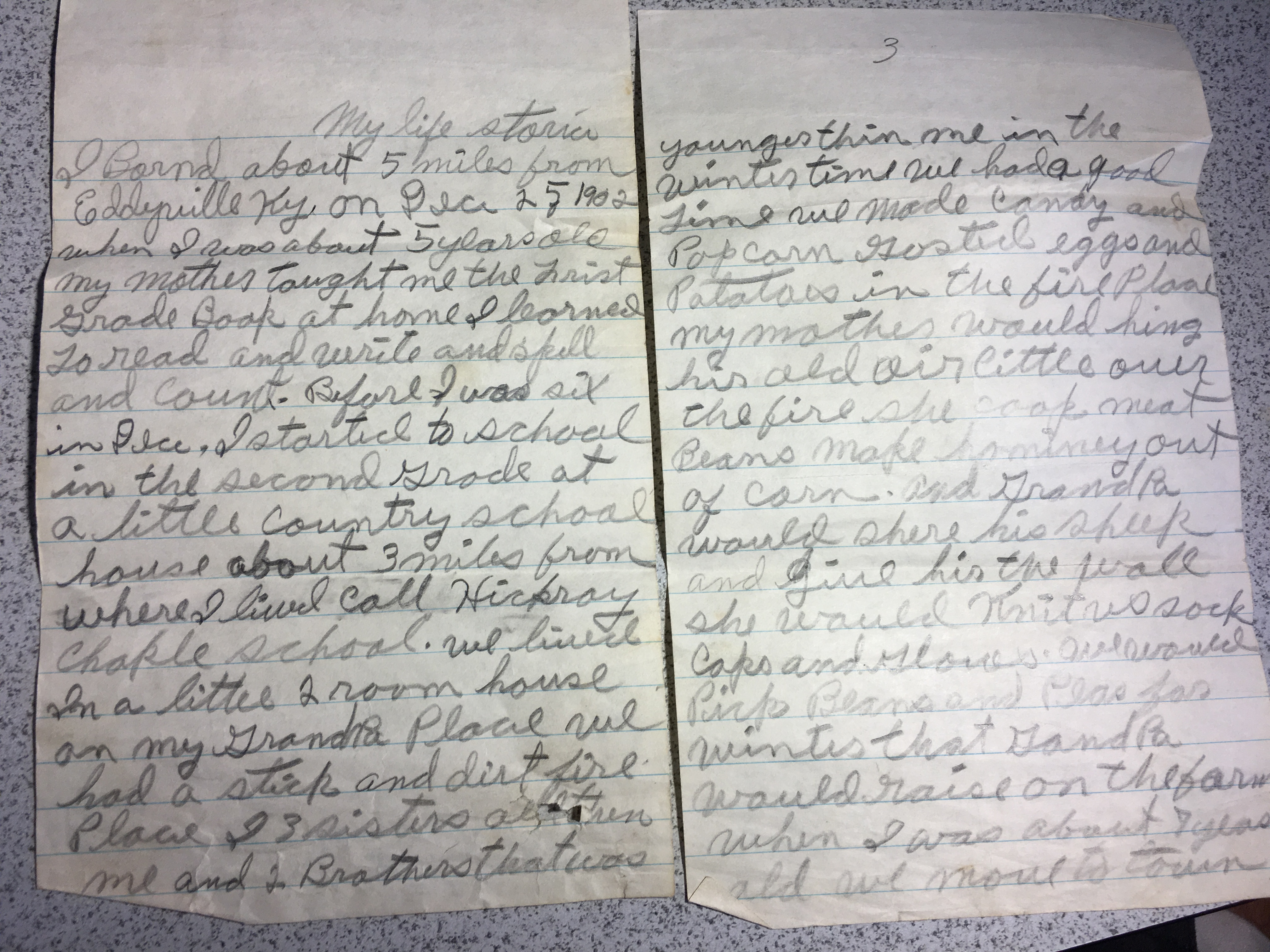

Two years ago I published a short eBook about my grandmothers. I am now making it available for free here.

Kentucky Wonders

Recollections and Recipes of My Rural Grandmothers

By Wade Kingston

Copyright © 2015 Wade Kingston

All Rights Reserved

Dedication

For Gola and Esther

Thank You

I would like to thank Helen Roulston. She has been a teacher, a mentor and an inspiration.

She has also been a terrific editor and a loyal friend.

Prologue

I grew up in rural western Kentucky of the 1950’s and 60’s. We didn’t have much money, but we had a lot of family. As a child I loved every member of our family, none more than my grandmothers.

I learned from my grandfathers by working beside them. From Grandpa Kingston I learned how to farm everything from corn to tobacco. And though I’m no Abe Lincoln, Grandpa Hammons taught me to swing an ax like I meant it. My grandfathers worked hard to provide for their families, and they had difficult years. We tried to be understanding when they were short-tempered. In truth, they could sometimes be grumpy old men.

My grandmothers were different. In many ways their lives were more difficult than their husbands.’ They shared all the hard work with the added burden of childbirth. But they still managed to be warm and loving women. Grandchildren were greeted with a smile and a hug; their persistent questions were patiently answered. Most of what I know of our family history and country life I learned from my grandmothers.

Gola Kingston and Esther Hammons were born at the dawn of the 20th century. Gola spent her entire life in Kuttawa, Kentucky, and Esther spent hers in nearby Eddyville. These two small towns are only a few miles apart in Lyon County–at the west end of the state. The land is a jumble of wooded hills, fertile lowlands, and water. It’s blessed with rushing brown streams, rivers and lakes.

My grandmothers lived in a remarkable century. Horse-drawn buggies were still in widespread use when they were born. When they died the internet was just getting fired up. They made it through the Great Depression, two World Wars, the Korean conflict, the Vietnam era, and countless family dramas. There were exciting times, emotional episodes, and unexpected events.

Gola had twelve children; Esther had seven. There were many grandchildren, of which I am but one. Each of us has our own memories, of course. These are only mine. I don’t list all those children and grandchildren for one simple reason–I wanted to focus on my grandmothers, and had I begun going down that rabbit hole I likely would never have finished.

I knew my grandmothers in the last third of their lives. By then they were full of stories and sentimental memories, and we made new ones together.

This short book contains ten short stories or remembrances for each grandmother. And each story has a related recipe. The first half is Grandma Gola’s and the second half belongs to Grandma Esther.

A Front Porch Memory and Green Beans

Family Reunions and Cornbread Dressing

Green Thumbs and Simple Sauerkraut

Hunting Cows and Scratch Pancakes

Hog Killing and Crackling Cornbread

Lumpy Snakes and Steak with Gravy

Gola’s Christmas and Bourbon Balls

Hunting Ginseng and Elderberry Wine

Cemetery Picnics and Blackberry Cobbler

A Two-Inch Thorn and Boiled Frosting

A Handkerchief of Pennies and Snow Cream

A Drowning and Pots of White Beans

A Railroad Man and Cherry Preserves

A Town Disappears and Wild Mustard Greens

Goosebumps and Fried Green Tomatoes

Esther, Jesus, and Red-Eye Gravy

Counting Train Cars and Biscuits

Part One – Gola

Gola May McKinney was born on September 17, 1905. Her parents were John McKinney and Holly Zollinger McKinney. John was born in Livingston County, Kentucky, in 1851. Holly was born in 1877. John and Holly had six children–three boys and three girls.

The year Grandma Gola was born Einstein wrote his theory of relativity. Theodore Roosevelt was inaugurated as the 26th president of the United States, and Franklin D. Roosevelt married Eleanor.

Grandma was a spindly-legged seven year-old when the Titanic sunk. Teddy Roosevelt was shot that year but didn’t die from it. Woodrow Wilson was elected president; Arizona and New Mexico became states.

Gola was a thin child, with high cheekbones and freckles. She braided her long brown hair each day and roped it around her head. She did her chores without complaining. Young Gola had a sense of humor and loved to joke. She was not above pulling pranks on her siblings.

She turned sweet 16 in 1921. Congress declared WWI officially over in July of that year. The first burial was held at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. “Behave Yourself” won the Kentucky Derby, and a first-class stamp cost two cents.

In 1924—the year Gola married John—unemployment had dropped to 5%, the summer Olympics were held in Paris, and the first-class stamp was still two cents.

A Front Porch Memory and Green Beans

As to Gola’s marriage, I remember when she told me about the first time she saw John (my grandfather). Grandma and I were sitting on her front steps at the farm on Panther Creek. I was 12. We had picked beans from the garden across the gravel road. It was a blistering hot day, as it often is when green beans ripen. We picked them in a hurry against the heat and retired to the porch to break them. It was late afternoon. The shade from the huge maples that flanked the porch was more than welcome.

“Look what hid in my apron,” she said. Reaching into her pile of beans she lifted a green snake by its tail and flung it into the yard. It glided away through the withered grass as Grandma cackled. All of a sudden she gazed off into the distance as if she were daydreaming. Her voice grew solemn.

“I was breaking beans with Mother the first time I saw John,” she said. “It was the summer of 19 and 21. It was hot like today, and down the road came a boy on a pony. When he went by he gave me a look and tipped his hat. He rode on by down the road, and I said ‘Mother, who was that young man?’ And Mother said, ‘Why Gola that was John Kingston.’”

Gola’s Southern Style Green Beans

Ingredients:

Fresh green beans, rinsed and broken* (fill pot 2/3 full)

1 ham hock or 2 tablespoons of lard

1 yellow onion, peeled

Salt and ground black pepper to taste

Directions:

Place all ingredients in a large pot and add about 6 cups of water. Water should cover beans by a couple of inches.

Cook—uncovered–on medium heat until beans are tender, and onion is cooked through and falling apart. The water should have boiled down even with beans. (The thickened juice is excellent by itself sopped with fresh hot cornbread.)

*My Grandmothers’ recipes were old-school. People ate what they wanted in her day–lard, sugar, eggs, and flour–because they burned it off daily. Farm work required a tremendous number of calories. No one was concerned with cholesterol or diabetes. They cared more for how food tasted, and if it “stuck with you” for hours in the field. You can’t have a salad and chop corn all afternoon.

All these recipes contain ingredients she used back in the day. Of course, you may adapt them yourself using healthier ingredients. Also, her green beans and onion were picked fresh from the garden. As you know, there is nothing as good as home grown, “fresh from the garden”. Her ham hock or lard came from hogs killed on the farm. (You can still find all these ingredients at groceries today or a trip to a farmer’s market will get you as close to her delicious fresh dishes as possible.)

***

Family Reunions and Cornbread Dressing

Gola McKinney and John Simeon Kingston were married in 1924. The wedding took place at a farmhouse on Panther Creek Road—what we in the family called “the old Walter Sizemore place.” Grandma was 18.

Within a year they welcomed the first of 12 children, all born at home without a doctor. Grandma never had medication during her deliveries–no epidural, spinal block, tranquilizers, narcotics, or injections. John’s mother, Jane Kingston, usually served as midwife. All twelve children had healthy childhoods and grew up to have their own families. (In fact, Dad tells me he can never remember my grandmother ever being ill. As a child I can remember the day in the late 1960’s when Grandma returned from the doctor. She had just gotten her first shot ever that day. She was 65.)

Years later I looked forward to the large family reunions. Half of Grandma’s family lived in Lyon County, and the other half was divided between Louisville and Indianapolis. I was in awe of the city cousins. They always seemed superior to us rural folk. They had flashier clothes, newer cars, and the latest Beatles records. We only had at most a few hours (sometimes a weekend) in which to get to know our city cousins. If you added up all the time I’ve spent with them, it probably amounts to less than a week.

Yet, we had our grandparents in common, and I liked all my cousins. I was fascinated by my glamorous city aunts, with their 60’s hairstyles, sequined sunglasses, and blue eyeliner. They looked like Hollywood to me, but they all reverted to “down home” types again around my Grandma. They jumped in the kitchen to help, painted fingers flying and metal bracelets jangling. They trotted to the outhouse as though they did it every day back home.

During summer reunions Grandma’s yard was usually full of screaming kids. There were dozens of us. We tried to cram a year’s worth of play into a single weekend, since we were never certain when we would see one another again. We climbed trees, hung upside down from limbs, and whooped about like savages. We seldom had baseball bats or balls–just our own ingenuity.

The 4th of July reunions are best remembered for the barbecue. One year, a couple of days before the holiday weekend, I walked with Grandpa John down the dusty road to my uncle’s farm. I think I was eight. I watched my uncle lead a white goat to the big oak tree by the pond. They hung the goat upside down from the lowest limb, its head dangling two feet from the ground. I didn’t know what was happening, so I was a bit confused when they put a bucket under its head. Then Grandpa stepped up with a large knife and slit the goat’s throat. It made one short bleat, and then the bright red blood poured as if from a faucet, down into the bucket.

Grandpa had a large brick pit with a hinged metal lid. He dressed out the goat and put it on the pit along with pork shoulders and a few chickens. Every few hours he went out to check that the hickory chips were smoking properly. Grandma made the sauce, and it was delicious. When the city kin arrived–usually on a Friday evening—the yard was foggy with that delicious smelling smoke. Everyone told Grandpa how good the goat meat was, but I wouldn’t taste it. I couldn’t get the image of the helpless goat getting its throat cut out of my head.

I loved the pork barbecue, fried potatoes, baked beans, and cole slaw of summer. The “thunder and lightning” salad, wilted lettuce, and green onions fresh from the garden, fresh cucumber slices swimming in vinegar and black pepper, saucer-sized tomato slices warm from the garden, and the ubiquitous pot of white beans, with corn bread and relish on the side. Everything was topped off with homemade ice cream and fruit cobblers. Foot tubs filled with bottled soft drinks in ice water were especially tantalizing to the kids. It sounds funny today, but back then we only had soft drinks on special occasions–like picnics or holiday reunions.

If the summer food was good, the fall holiday fare was even better. At Thanksgiving and Christmas we were sure to have my Grandmother’s sublime turkey and dressing with giblet gravy. There was also crispy fried chicken and a tender baked ham with its own salty-sweet crust.

On the side we had all the year’s bounty from the garden–fresh sauerkraut, canned green beans, corn, tomatoes, okra, and buttery yams. A large bowl of whipped potatoes was added to each end of the table–saucers with slabs of fresh-churned butter near them. Mason jars of new pickles, bowls of sliced beets, and black-eyed peas swimming in pork fat were scattered about.

The desserts filled their own table. Pecan pies, chocolate and lemon meringue pies, and yellow cake with fluffy white coconut frosting crowded the table. The kids drooled over a three-layered German chocolate cake. We washed it all down with gallons of iced tea (sweetened, of course), lemonade, and pots of strong coffee.

The family was so large that the women and children had to wait until the second seating. I used to pray silently that the men wouldn’t eat all the pecan pie before I could get a slice. To my way of thinking there could never be too much pecan pie.

Gola’s Cornbread Dressing with Giblet Gravy

Ingredients for dressing:

1 large skillet of cornbread, baked and cooled

1 pan (8) of biscuits, baked and cooled

1 cup of diced onion (small pieces)

1 cup of diced celery (small pieces)

2 raw eggs

Turkey broth/chicken broth

Sage (in the can, and do buy a fresh can)

Milk

Salt and pepper

Directions:

- Preheat oven to 425° F. In a saucepan add 2 cups of whatever broth you have on hand (broth from the turkey is OK, or canned chicken broth) and add the onion and celery. Cook until tender.

- In a very large bowl crumble up the cornbread and biscuits by hand. Pour in the cooked celery and onions. Add two raw eggs, and sage to taste. (Some people like a lot, others just a little). Salt and pepper to taste, and add just enough milk to bring the whole thing to a pouring consistency.

- Pour dressing batter into large greased skillets or casserole dishes. Bake for 25 to 30 minutes, or until dressing is set butnot dried out. Remember: the breads are already cooked, so you are really just making sure the eggs are done and the whole thing is heated through and set.

Ingredients for giblet gravy:

Turkey or chicken broth

Giblets from inside the turkey (the liver and gizzard)

2 boiled eggs

Cornstarch

Salt and pepper

Directions:

- Start by cutting up the liver and gizzard (which you cooked alongside the turkey) into small pieces. Add the pieces to a saucepan with two cups of broth (turkey or chicken).

- Boil a couple of eggs separately and cut them into pieces and add to the meat and broth. Bring to a boil and add enough cornstarch to thicken. The amount of cornstarch will depend on how much gravy you are making, of course. Salt and pepper to taste.

- Pour giblet gravy over the southern style cornbread dressing, just as you do with mashed potatoes. A true southern style delight!

***

Green Thumbs and Simple Sauerkraut

Grandpa John was an uneducated man, which was not unusual for farmers in 1924. He could neither read nor write his own name. (I recall as a child that I witnessed him make his “X” on a farm contract.) But he was smart in the ways that counted, and he was a hard worker. By the time the Great Depression arrived–six years after the wedding–he had a 109 acre farm about five miles from the little town of Kuttawa. It was part bottom land, part hilly pasture, with plenty of wooded area left over. The land sustained the growing family in the hard years to come.

My dad, Russell Kingston, was born on the first day of winter, December 21, 1931. He was the fifth child, arriving in the cold just as the Depression was worsening. Surprisingly, most of my dad’s memories of early childhood do not center on deprivation. Instead, he remembers the inventive ways the family got around shortages. His voice is full of admiration whenever he speaks of the bounty brought forth on the farm.

Dad recalls how the older children looked after the younger children as Grandpa and Grandma worked the fields. This was nearly 20 years before Grandpa got his first tractor, so the fields were plowed with mules. As the corn grew the weeds were “chopped out” with hoes. The work was back breaking and never-ending, especially for Grandma. She was often pregnant, and her labors didn’t end when the sun went down.

Grandma Kingston always had several gardens. The largest garden was a fenced area directly across Panther Creek Road from her house. It was prime bottom land, so rich it needed very little fertilizing.

The garden gate had two wooden posts; the one on the right had a hole in it where bluebirds nested each year. Once inside the gate, on the left was a long row of mature apple trees. I never fully appreciated her apple trees when I was a boy, but I certainly wish I had them now. There were various types, the limbs so laden with apples they were often propped up with boards.

Grandma had apples to spare. The ground under the trees was covered with rotting fruit and swarming yellow jackets. She canned apples, made applesauce, and dried slices of apples between screens, which she laid in the sun. Bees and wasps crawled over the screens trying to get to the fruit. The aroma of cooking apples and cinnamon wafted from her kitchen windows.

Beyond the row of apple trees, the long rows of vegetables were neatly laid out. The brown soil had been carefully tilled for so many years that it was soft and fine. Carrots and turnips grew large in that soft soil, and so did potatoes. As a child I was surprised to learn that peanuts grew underground. Tomatoes, lettuce, onions, cabbage, beets, garlic, squashes, melons, okra, and sweet and hot peppers were all given adequate space.

Grandma hit the garden early, when the dew was still on the grass. She said that the best time to weed a garden was before the sun was high. That way the sun killed the weeds left lying between the rows. The worst time to weed was right before sundown, for crabgrass could take root again overnight—especially if it rained. She was right, of course.

After carefully tending her garden, Grandma made stops at other gardening spots on the way back to the house. In addition to the main garden, she had a “side” garden near the house where she grew herbs. There was a large dill plant by her bedroom window. I loved to mash its tender fringes and inhale it. Grandma grabbed her short hoe—always at hand—and made quick work of any weeds that dared to pop up overnight.

On the western side of the driveway were cherry trees, and behind the house were pear trees. The cherry trees were often thick with cardinals, bluebirds and jays, flapping and fussing at one another when the fruit was ripe. There was always a rush to get the cherries before the birds ate them all. When I was about eight I climbed up one of the pear trees and was attacked by a blue jay, which had a nest near the top.

The area directly outside the kitchen was reserved for Grandma’s beefsteak tomatoes. She planted them near the door so that when dishwater was thrown out it watered the plants. Those tomatoes lived up to their “dinner plate” name. Behind the beefsteaks were roses and dahlias. Around the yard were perennials and shrubs of every type. I measured the seasons by whatever was blooming at the time in Grandma’s yard. The colors and fragrances were intoxicating.

I especially liked seeing the peony bushes rise up from the ground in early spring; the tender pink shoots seemed to grow inches every night. But there were old English roses, “Seven Sisters” roses, Bridal Wreath, hydrangeas, and lilies by the ditch full. Zinnias, marigolds and sunflowers grew in veritable waves. Pots of portulaca lined the well. Beds of petunias overran the footpaths. It was as if Grandma couldn’t tolerate a bare spot of ground. If something could be growing on it, she took the time to make it happen.

Whenever any of her 12 children visited, Grandma grabbed a paper bag and plucked tomatoes and fruits as she walked them to their car. Everyone left with a bag of ripe produce.

Her tomatoes were the largest, her flowers the healthiest. She used manure from various farm animals as fertilizer, but claimed the best came from chickens. She got the manure from under the roosting poles in the henhouse. Though I sometimes helped her scoop it up, it was altogether an unpleasant job. It stank in there, and if you touched the poles you risked getting chicken mites on you.

The henhouse was one portion of a long rectangular building. The first “room” in that building was a corn crib, with its musty odor. The sun shining through the slats highlighted shafts of swirling dust. Though we weren’t supposed to we often sneaked in there to play. The second room was for farm tools, and was usually locked. Behind the third door was the henhouse, with nests on the left and roosting poles on the right. The last section was a “two-holer” outhouse. The outhouse sometimes had Black Widow spiders in webs high in the corners. We hurried when “doing our business.”

One day I was helping Grandma lug one of her tremendous cabbages back to the house. She was about to begin making sauerkraut. “This cabbage is bigger than the ones in the store,” I said to her. And then she told me that once she had grown a cabbage so big it was in “Ripley’s Believe It or Not.” Now, Grandma loved a joke or a tall tale, so I laughed when she told me about Ripley’s and said “Uh huh,” as if I didn’t believe her. A few days later she brought out an old yellowed newspaper clipping of a Ripley’s cartoon. On it was a drawing of Grandma with an enormous cabbage. The caption read, “55-Pound Cabbage Grown by Gola Kingston of Kuttawa, Ky.” She laughed when my jaw dropped. I never doubted Grandma again.

Gola’s Sauerkraut

Ingredients:

Fresh cabbage heads

Pickling salt

Directions:

- Wash and core the cabbage heads. (Grandma made enough sauerkraut to fill a 10 gallon crock, but I suspect you will make a lesser amount.) Shred the heads, or if you don’t have a shredder you can slice the cabbage very finely with a knife. You can certainly make sauerkraut in a gallon glass jar. It’s fun to watch the cabbage become sauerkraut.

- Place 3 or 4 inches’ worth of shredded cabbage (5 pounds of it) into the crock and sprinkle 3 tablespoons of salt over it. Repeat until all the cabbage has been layered into the crock. At that point grandma poured about 1 cup of boiling water over the last layer, then added the last layer of salt and covered it with clean cheesecloth. She pressed each layer down hard as she went. It needs to be packed in there tightly.

- You will need to weigh the cabbage down. Grandma had a very heavy crock lid that fit inside her crock. She placed it on top of the cabbage and added a couple of clean bricks on top. As the cabbage wilted and shrank the lid settled further down the crock.

- Check the container every couple of days. If excess juice seeps out, pour it off. Keep the liquid level with the top layer of cabbage. Watch for any sign of scum and remove it immediately. It should be sauerkraut after a couple of weeks, though Grandma let hers stand for about a month before serving. Nothing tastes better than homemade!

Note* Grandma had a cool room in which to store her big crock of sauerkraut–the room farthest from the wood stove. But she canned sauerkraut in jars also, to give to family when they visited.

***

After supper Grandpa John washed his feet in a foot tub. Then he relaxed in his cane chair with a pipe. Grandma kept going. She saw to it that the children were clean, their clothes scrubbed. Dishes were washed, food put away. Often Gola sat up mending clothes. In winter she quilted late into the night–her head bent over the frame–a kerosene lamp lighting the stitches.

Their attic was insufferably hot during the summer–good only for drying fruits and vegetables. But it was transformed into Grandma’s workshop during winter. As a child I read the newspaper aloud to her or threaded her needles as she quilted. Jars of butterscotch-colored peaches lined the walls of the quilting room. Cheesecloth bags of dried apples and strings of red peppers hung from the ceiling. In winter Grandma’s houseplants filled the dormers, warmed by westward-facing windows. Tables stacked with knitted doilies, and hook rugs made from Bunny Bread sacks sat in the corner. Everywhere you looked were examples of Grandma’s handiwork.

As a grown woman, Grandma Gola was of average height. She was lean and willowy her entire life because she ate little and worked much. Many times I noticed Grandma–after the family was seated–put a small amount of one food in a bowl and eat. She rarely joined the family at the table. She claimed she was full from tasting everything.

I’ve often wondered if Great Grandmother had drummed it into Gola’s head that “Idle Hands are the Devil’s Workshop”. The few times I actually saw my Grandmother relax came late in the evenings, long after dark. During the daylight hours she was in constant movement.

I always thought of Grandma Gola as a pioneer woman. She was usually in a thin cotton dress, to which she added a sun bonnet when gardening. At that point she looked just like those women who rode out in covered wagons into the west. It seemed to me she could do anything. I believe she could have been set down in the wild woods anywhere and survived.

Grandma and Dad spent many hours in the woods in the late 1940’s, digging May apple. The May apple root lies near the top of the soil, so it isn’t particularly hard to dig, but it sold for only pennies per pound. I can’t imagine how many pounds of it Grandma had to dig, but she saved enough money and bought her first set of dentures with it in 1948. They cost $95. (As a child I thought Grandma had the nicest natural teeth, until I caught her putting them in early one morning.)

Just as I would do decades later, Dad often accompanied Grandma to her garden. One day they ran up a covey of quail, and Grandma said to Dad, “I’m going to catch those quails, Ducky.” (Dad had been given the nickname “Ducky” as a child because of his fondness for wallowing in every mud puddle around.)

“You’re going to shoot the quail?” said Dad.

“No, I’m going to catch them,” said Grandma. Dad couldn’t imagine how that could be done, and he told his mother as much. Grandma just grinned and said, “You watch.”

They returned to the house and got tobacco sticks. Grandma dug a depression in the ground near where the covey had flown. Then she used the tobacco sticks to construct a teepee-like structure over the depression in the ground. Then she dug a trench out from beneath the teepee, extending it about a foot. Then she hid the trench with a board.

The next morning Grandma awakened Dad and said, “Let’s go get the quail.” Dad rubbed his eyes and said, “How do you know we got any?” Grandma replied, “I hear ‘em whistling.”

When they got to the trap there was one quail sitting on top of the teepee, and it flew off. All the rest were inside the coop. Grandma removed the plank and ran her hand inside and brought out a quail. She twisted its head off and handed it to Dad, who put it in a bag. They ended up with every quail in the covey, except for the one that flew off when they arrived.

Dad and Grandma would often walk to the Iuka ferry. That was many years before the Cumberland River Bridge was built near Lake City, Kentucky. Along the way they picked up soda bottles from the side of the road, and sold them at the little store in Iuka. There was often enough “bottle money” to buy a sandwich, and one time Grandma had enough for them to catch a bus. They rode it to Smithland so Grandma could visit her sister.

Grandma and Grandpa never had a real vacation, nor did they take trips together. Grandma went to Indianapolis once or twice to visit children. Grandpa also went there, but he never had a driver’s license and depended on others for transportation. (In fact, none of my four grandparents ever had a driver’s license.) Of course, Grandpa Kingston did drive his tractor on the farm, which didn’t require a license.

The Great Depression hit everyone hard in the early 1930’s. Even farmers were unprepared for the severity of it. After one trip to town to buy meat, Grandpa returned home empty handed. There simply was no meat to be found. Grandpa vowed not to be caught “with his britches down” again. He raised more livestock, and Grandma planted larger gardens.

The very next year they butchered 12 hogs. Grandma canned hundreds of jars of produce. Word got around about this amazing bounty, which existed at a time when people were starving in the cities. The press showed up and took pictures. Newspaper articles–depicting a smokehouse overflowing with abundance–highlighted the plight of city dwellers when compared to farmers.

The Depression caused people to get creative. Grandma raised her own popcorn, and sent the boys out looking for bee trees. Honey was not to be found in the stores. She picked as many blackberries as possible and sold them by the side of the road for extra cash to buy needles, thread, and other items that were either unavailable or too expensive. The food was seasoned with lard or butter, both produced on the farm. Vegetable oil and Crisco was simply too scarce to buy. Some of the children actually got sick of butter. (It’s hard for me to imagine such a thing.)

A Korean POW and Dumplings

Grandma and Grandpa Kingston got through the Great Depression and World War II without losing anyone, and then came the Korean War.

My dad, Russell, went into the army at 18–right after the Korean conflict began. He was captured almost as soon as he got to Korea, and remained in a camp in North Korea for the duration of the war. He ended up being held for 33 months, in a war that lasted only three years (Technically, it has not ended.) Several of Grandma’s sons eventually joined the service, but none were allowed overseas after Dad was captured.

Grandma missed my dad terribly, of course. She went for several months at a time without any word from him. In the P.O.W. camp Dad got only rare letters from home, however much Grandma wrote. The enemy kept her letters to him, sometimes releasing several at a time. Many sentences were marked through.

After one particularly long period without hearing from Dad, Grandma had a dream that a dove flew to her window with a letter in its beak. It was from my dad. She awoke and thought little of it. That very day she got a letter from Dad and in one corner of the envelope was a dove printed in blue ink. (Many years later she gave me that letter, which I still have.)

When Dad was finally released from North Korea he was in a pitiful shape. He was emaciated, had suffered frostbite and dysentery, and couldn’t eat any solid foods. He had shrapnel wounds and metal in various parts of his body, which he still carries to this day. But he was in one piece and his spirits were high when he arrived back in Kuttawa.

The county threw a big celebration, calling it “Russell Kingston Day”. There was a parade—well-attended—with Dad sitting in between Grandma and Grandpa on the back of a convertible. Politicians from around the state spoke, but Dad just wanted to get back to the farm.

For weeks after his return Grandma babied him. She made all his favorite foods that were soft enough to eat. He tells me he most recalls how good the chicken and dumplings were.

Gola’s Chicken ‘n Dumplings

Ingredients:

1 large fresh chicken (3 lbs. or larger)

2 stalks celery

Salt

Water

Biscuit dough (see Esther’s Homemade Wood Stove Biscuits)*

Directions:

- Place the entire chicken (cleaned, with insides removed) into a Dutch oven. Add water to cover, celery, and 1 teaspoon salt. Bring to boil.

- Reduce heat and simmer about an hour until tender. Remove chicken from broth and set aside. Discard celery. When chicken has cooled, tear the meat with your fingers into small pieces. Discard bones, and set the chicken meat aside.

- After making biscuit dough, roll out the dough until it is about ¼ inch thick. Cut into strips about 1 inch by 4 inches.

- Drop strips, one by one, into the simmering chicken broth. Then add chicken pieces and cook for about five minutes.

*My mother has used bought biscuit dough.

***

Hunting Cows and Scratch Pancakes

When I was about eight we moved into our new home, just a few hundred feet up Panther Creek Road from Grandma’s house. Grandma had several head of cattle, and three of the cows were giving milk. The lead cow had a big bell around her neck. It became my job to go out at the crack of dawn and find the cows and herd them in for milking.

As I went through the gate to find the cows each morning Grandma yelled at me, “Don’t run those cows! They won’t drop their milk.”

The cattle were often in a back pasture, and weren’t always willing to be herded. Cows are dumb creatures. To get them moving down the paths sometimes meant laying a switch across their backs. I watched as they trotted off toward Grandma’s, their heavy milk bags swinging back and forth. On dim, foggy mornings the grass was chilly and wet with dew. My shoes and socks were soaked through by the time I returned for the milking.

Grandma taught me to milk cows, though I couldn’t get much milk from the teats. My hands were small and worn out long before the cow went dry. Grandma finished for me, her practiced hands getting strong jets of milk to froth into the pail. Her cats waited patiently. Grandma occasionally sent a stream of milk in their direction and cackled as they licked it off their whiskers.

For my efforts at gathering the cows our family was rewarded with a jug of fresh milk whenever we needed it. At times Grandma had butter or buttermilk to spare. The best treat for me came on the mornings when Grandma made her scratch pancakes.

When I didn’t have school Grandma made breakfast for me after the milking. If I had a choice I asked for pancakes, partly because they were so good, and partly just to watch her make them. She had made them so often she knew the ingredients by heart. It amazed me that she could remember everything so exactly without looking at a recipe.

She cradled the bowl in her left arm, as if it were a baby. She carefully mixed the batter until it was silky smooth. When the last pancake left the skillet and the plate was set before me, it looked like the photo on the instant pancake box at home. But Aunt Jemima had nothing on Grandma. I still use her scratch recipe to this day.

Gola’s Scratch Pancakes

Ingredients:

1 ½ cups all-purpose flour

3 ½ teaspoons baking powder

Pinch of salt

1 tablespoon of sugar

1 ¼ cups milk

1 egg

2-3 tablespoons of melted butter

Directions:

- Sift all the dry ingredients into a large bowl. (Grandma always sifted her flour, because she had the old-fashioned cupboard with the flour bin and the sifter built in underneath.) Make a well in the center of the dry ingredients and pour the milk, egg, and butter into it. Beat vigorously until the batter is smooth with no lumps. (Grandma used a whisk). Add a small amount of milk if it’s too thick to pour.

- Heat your griddle or cast iron skillet over medium heat. Add a small amount of shortening. Grandma used lard, but hey, that’s what they had in the country. When the griddle is hot, pour enough batter—I’d guess it was ¼ cup—at a time to make a medium sized pancake.

- The pancake is ready to flip when it has “set” around the edges and the top is full of holes. After flipping, the pancake should be cooked through in about a minute. Serve with butter and syrup. (Often we didn’t have “pancake” syrup, but sorghum worked quite nicely.)

Note* Grandma sometimes used buttermilk when baking biscuits, cornbread, or pancakes—and it was amazing. Her buttermilk was “homemade,” literally the milk left over after churning butter. It was not as thick as the buttermilk we purchase today. I find that when I bake with today’s processed buttermilk it tends to make the cornbread, biscuits, etc. very heavy. So I recommend using half buttermilk and half 2% milk. That way you get the flavor without the heaviness. Or, as an alternative you can use buttermilk but add a pinch of baking soda.) Another tip is to let your batter “rest” a few minutes before making your pancakes. It does seem to help.

***

Hog Killing and Crackling Cornbread

In the fall, when the pigs have reached a good size and the weather has cooled, it’s hog-killing time on the farm. Grandpa often had several hogs to kill at one time. There was a bunch of family members there to help. The men killed and cut up the hogs, then set about salting or smoking portions of the meat. The women made cracklings and sausage.

One year Grandpa decided to kill his brood sow. She had given him many litters but was now so big her teats dragged on the ground. I watched as Grandpa shot her between the eyes with his .22 rifle. She didn’t fall as much as just roll over. After killing them, they hung the pigs upside down and drained the blood. Then they lowered them into a 55-gallon drum of boiling water so they could scald the skin and scrape the hair off.

I was too small to be of much help, though I did turn the crank on the sausage grinder. All the miscellaneous pieces of pork were placed in a tub, and from the tub we fed the pieces into the grinder to make pork sausage. Spices were added and mixed by hand after the meat was ground. Then the meat was molded into log shapes and wrapped with freezer paper. Grandma carefully wrote the date and whether the sausage was “hot” or “mild” on the packages.

The best pork as far as I was concerned was the tenderloin. It’s unbelievably delicious, tender, and flavorful when eaten fried, fresh from the hog. We kids were eating so much of it that Dad told us it might make us sick. I’ll never forget that flavor.

There was always a lot of leftover fat when the pork belly (bacon) was trimmed out. It was cut into cubes and thrown into a huge cast iron kettle set over a fire in one corner of the back yard. As the “cracklings” cooked and rendered out the lard you could smell them all over the yard. Kids came running. Fresh hot cracklings are crunchy and lip-smacking good.

After the cracklings were removed from the big iron pot, the hot rendered fat was poured into large tin buckets with lids. After it cooled and solidified the lard was used all year as cooking oil.

The cracklings, when not eaten alone, often went into a southern favorite–crackling cornbread.

Gola’s Crackling Cornbread

Ingredients:

2 cups self-rising cornmeal

½ cup all-purpose flour

2 ½ cups buttermilk (or whole milk)

2 eggs

¼ cup melted fat (lard)

1 cup of cracklings

Directions:

- Put fat in a cast iron skillet (9 inch) and heat in a 425 degree F. oven for about 4 minutes.

- While skillet is heating, combine dry ingredients; then stir in the wet ingredients. Stir just until there are no lumps.

- Add to hot skillet and bake for roughly 25 minutes. Cornbread should be firm when pressed and light brown on top.

It’s best to let the bread sit a few minutes before slicing and serving.

***

Lumpy Snakes and Steak with Gravy

Grandma gave me a few marigold seeds so I could grow something. I planted it in probably the worst location, and when I told her it wasn’t growing, she told me to fertilize it. “What with, Grandma?” I asked. “Cow manure is good,” she said.

Our house was surrounded by a pasture full of cattle, so I was eager to use cow manure. I found a fresh pile–and in case you don’t know, fresh cow manure is runny and sloppy. It’s easy to transport in a shovel, so I did. I literally poured it around my marigold and let it be. Of course, it dried into a hard patty and stuck to the marigold stem. As the stem grew upwards, it took the cow patty with it. I came out one day and saw what looked like a brown plate, surrounding the marigold stem about a foot off the ground.

I loved living near Grandma and Grandpa. After we moved close to them, there was hardly a day–especially in summer–that I didn’t see Grandma and Grandpa. Grandma coached me in my gardening efforts, and helped me get my bantam chicken collection going. In summers I helped Grandpa “work” the tobacco.

I had been helping Grandma gather eggs when I became interested in chickens. She had a large henhouse with two rows of nesting boxes which met in a dark corner. The lower row was shaded by the upper row, so you couldn’t see into the box all that well, especially the one in the corner. Sometimes when I put my hand in the box there was a hen in there. She might peck me hard, or fly out of the box in a big, screaming commotion.

One time I reached into the lower corner box–the one that was the darkest–and it didn’t feel right. It was smooth and cold and it moved. I was so scared I immediately jumped back and yelled. Grandma got a hoe and pulled out a long chicken snake. You could see three lumps in the snake where the eggs were. Grandma said it might have swallowed more given time. She chopped its head off and fed it to the hogs.

It was Grandma who taught me that chickens lay one egg a day (if you’re lucky), and that once the hen “sets” it takes 21 days for the eggs to hatch. I eagerly marked my calendar whenever one of my own bantam hens began setting, and waited. When the chicks started to hatch it seemed like it was taking them forever. I wanted to help them out of their shells, but Grandma told me not to do that. She said they had to do it themselves. Sometimes, for reasons unknown, a chick died before getting out of its shell. The ants quickly found them.

I hated to lose even one chick, but Grandma said it was nature’s way. “They have to follow their mother around all day,” she said. “They need to be strong right off.”

Before Old Kuttawa was flooded by TVA and the whole town had to move out from under the new Lake Barkley, Grandma came into town each day to work at Peek’s BBQ restaurant. Though she could cook anything on the menu, I looked forward to her pies. The three pies on the menu that day depended on which ones she was in the mood to make. Usually it was chocolate, coconut, and pecan, though many times the restaurant sold out of all three. I always went in hoping there was a piece of pecan pie left.

Dad and I sometimes went there for lunch. Grandma often saw us through the window of the kitchen’s swinging door. Out she came, smiling and wiping her hands on her apron. Her long brown hair was braided and coiled about the top of her head. She wore wire-rim glasses and weighed maybe 100 pounds soaking wet. She smelled of smoked pork barbecue. (To this day whenever I smell the heavenly aroma of smoked barbecue I recall that old restaurant.) If I asked Grandma what pies she had, she smiled (she knew what I wanted) and say, “I’ve got one piece of pecan left.” (She always said just one piece was left. I wonder now if she said that to make me feel special, as if she had saved it just for me.)

You might think that a woman who worked in a restaurant all week wouldn’t want to cook on her days off, but Sunday dinners at Grandma’s were an event. After church the cars began arriving from both directions. Sometimes there were seven or eight people, sometimes three times that many. It never seemed to fluster her. There always seemed to be enough food and no one was turned away. We didn’t know what was going to be on the menu, but we knew it was going to be good. One of my favorite Sunday meats was one not often cooked—country style steak and gravy.

Gola’s Country Style Steak with Gravy

Ingredients-steak

2 pounds cubed steak

1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

1/2 cup dried onion flakes

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

1 1/2 teaspoons salt

3/4 cup of vegetable oil

- Salt and pepper steak. Coat steak in flour or shake with flour in a plastic bag. I often saw Grandma use an empty bread bag.

- Heat oil in skillet on medium. Fry a few pieces of steak at a time just until browned. (Do not over-cook)

- Place steak in a large casserole dish or pan. Sprinkle with onion flakes. Make gravy and pour over steak. (See recipe below).

Ingredients-Gravy

1/2 cup flour

1/4 teaspoon salt

2 1/2 cups water

- Add flour to the same skillet the meat was cooked in. (The skillet should still have oil in it). Stir on medium heat until flour browns but doesn’t burn.

- Add salt to flour mixture, then water, and continue cooking and stirring until well blended. Gravy should be thin. Pour thin gravy over steak and onion flakes.

- Cook in 350° oven for 1 1/2 hours, or until fork tender.

This gravy is so delicious over mashed potatoes as well.

***

Gola’s Christmas and Bourbon Balls

Grandpa Kingston may have grumbled about the expense, making a comment from his recliner behind the coal stove, but Grandma generally ignored him. At times she even fussed back at him. She would do Christmas her way, and he could like it or lump it.

It may have been Grandpa who went out on the farm and chopped down the cedar tree, but Grandma took over from there. She stuck it in a lard can filled with gravel, and then covered the can in tin foil. She wrapped the little tree with large colored lights, and added what few old glass ornaments she had. Then she wound strings of popcorn from bottom to top. She finished it off with shimmering strands of foil icicles. Last was a spray of artificial snow. A good deal of it ended up on the ornaments. The hot bulbs heated the branches, spreading the cedar smell throughout the house. You knew when you came in the back door that the Christmas tree was up.

I remember the joy of seeing that tree through the window on a cold winter evening. It was like a beacon calling out, “You may be cold out there, but in here it’s warm and cozy. The house smells of cookies and the coal stove is toasty.” One day there was nothing in that spot but a white curtain. Behind the curtains was a table covered with dozens of framed family photos. The next day the tree appeared like magic, fully decorated and packed around the base with gifts. Packages were piled against the trunk, right up into the branches. They slid down and spread out all over the linoleum floor. I gazed in wonder at the pile.

Grandma started her Christmas shopping weeks in advance. She bought gifts for each of her twelve children and spouses, along with all the grand-kids—and there were over thirty grand-kids even in the 60’s. Everyone got something–usually gloves, socks, or handkerchiefs—but it was always something practical and welcome. Just seeing my name on a package gave me a thrill I seldom experience these days.

Of course, Grandma did a lot of baking during the holidays. In addition to her usual cakes and pies, she made more candies and cookies. Ginger snaps, butter cookies, sugar cookies, oatmeal cookies, fudge, peanut brittle, divinity, and sometimes Bourbon balls. I confess I did not care for them as a child, but these days they are among my favorite.

Gola’s Kentucky Bourbon Balls

Ingredients:

1 cup chopped pecans

5 or 6 tablespoons of good Kentucky Bourbon

½ cup of butter, softened

1 box (16 ounces) of powdered sugar (confectioner’s sugar)

18-20 ounces of semi-sweet chocolate

Directions:

- Place the chopped nuts in a jar, or a bowl which has a lid. Tupperware works well, or a Mason jar. Put enough Bourbon in the nuts to just cover them. Let these sit overnight at room temperature. The nuts absorb that awesome Bourbon flavor.

- The next day (or the day after that) mix the softened butter and the powdered sugar together. Fold in the Bourbon-soaked pecans; then roll into small balls. Place on a cookie sheet and refrigerate overnight. (I have skipped this step by placing them in the freezer just until they were firm. Grandma never did. She was more patient, or maybe she knew something I didn’t.)

- Line a tray with wax paper. Melt the semi-sweet chocolate in a bowl over simmering water until it melts. Use a spatula to scrape the sides and keep it mixed well so it stays evenly melted. Use two spoons to roll each ball in the chocolate until coated. This takes practice, but it’s fun. Place the coated balls on the waxed paper; then chill them all in the fridge until the chocolate is well set and the balls are chilled through. Delicious.

Note—I have not included any of Grandma’s pie recipes. They were all delicious and my own favorite was pecan. There was nothing special about them, except for her pie crust. I don’t know how she made her pie crust, but they were always thin and crispy, almost like a cracker. Her pie crusts held up under the heaviest of fillings, even when overloaded with apples. Yet they were never tough.

***

A Red Mule and Popcorn Balls

One summer Grandpa’s mule became very sick. I watched as the old animal walked around in a never-ending circle. He walked around and around for days, plodding through the hot sun and humid nights. He didn’t stop.

When Grandpa discovered Toby making his circle, he called out to him. But Toby’s ears did not turn toward Grandpa, nor did he stop. Grandpa laid a strap across his broad back, but Toby appeared not to notice. Grandpa let him be after that. The veterinarian told Grandpa to just shoot Toby. Grandpa said thanks, that he might do that. But when it got right down to it he couldn’t. Grandpa told me, “Toby will come around.”

But he didn’t get well, and several days later he fell over dead. Grandpa chained Toby’s back legs to the tractor and hauled him off into the woods down by the creek. And that was the end of Toby. The sorghum press sat idle after that, but my memories of making sorghum were still fresh in my mind.

I thought about all the buttery sweet sorghum molasses I had sipped, hot from the pan. Toby had done all the hard work back then. He had pulled the planter, then the plow. And when the tall sorghum was cut, Toby hauled the bundles to the press. Then he was hitched to the press, where he walked around and around for hours each day. Grandpa fed the stalks into the mill, from which the sweet sorghum juices flowed.

Then the juice was poured into the top end of the “pan,” which was long and flat with vertical compartments designed to let the juice heat up and flow toward the lower end. A fire was kept under the pan, and the juices bubbled away. The aroma was heavenly. As the raw juice made its way through the compartments it was stirred and skimmed. When it reached the bottom end it was sufficiently reduced to syrup. It was then drained into buckets and set aside to cool. Trust me when I tell you there is no more divine taste than fresh-cooked sorghum hot from the pan.

Dad told me that when he was a child grandma cooked the sorghum until it made a ball. Then they took it off the stove and pulled it like taffy. Grandma took it outside when it was cold and draped it over the clothesline. When it hardened, Grandma took a butcher knife and hit those ropes so that pieces of hard sorghum fell into a pan. They ate the sorghum pieces like any other hard candy.

Dad also told me that Grandpa put a tin can of sorghum on the back of the wood stove. Meanwhile, Grandma made roughly 100 biscuits in large flat pans. They had hot sorghum and biscuits with slabs of fresh-churned butter. Dad said that Tony, his brother, grabbed a handful of biscuits, put a slab of butter on a plate, and poured hot sorghum over the butter. Then he sopped it with at least a dozen biscuits. Another brother, JB, got sick on butter and couldn’t eat it for the longest time.

What I remember most are the sorghum popcorn balls. Grandma and I were both night owls. If it wasn’t a school night I’d slip down the dusty road and watch Johnny Carson with her. She sat on a green vinyl ottoman close to the television. Grandma loved Carson and laughed heartily. She also liked Gomer Pyle.

On Friday nights after Carson we watched “Creature Feature” on Channel 5 out of Nashville. Grandma made popcorn–sometimes popcorn balls–and we sat glued to the screen. We both loved being scared; and right before the movie started Grandma usually said “Now if it’s about a doll or a cat, it will be real scary.”

Grandma could be mischievous. On many nights, as I headed out the door to walk home up that dark gravel road, Grandma whispered, “Don’t let old hairy arms get you!” As I flew up the road in my bare feet I imagined all kinds of monsters in the weeds lining the road. Every sound made me jump.

Grandma was also fond of ghost stories. I guess she wanted me to get home in a hurry, for she sometimes told me one of those as well. Once she told me a “true story, cross my heart.” She said one night she was walking home from working in the restaurant. (She got a ride the first five miles, but walked the last mile.) It was late and pitch-dark. She could barely see the gravel road. She got to one particularly dark place on Panther Creek Road, where no one lived when she heard a loud scream.

“It was just like a woman’s scream!” she said. “Real loud. It made the chills go up my arm.”

“What was it, Grandma?” My eyes were about to pop out.

“Why, it was a panther!” She said. “Don’t you know there’s panthers living here on Panther Creek?”

I don’t know if that’s how Panther Creek got its name, but for many years I listened for the sound of a woman screaming. And when it came time for me to go home at night, I got there in a hurry.

Gola’s Sorghum Popcorn Balls

Ingredients:

1 cup sugar

1/4 cup pure sorghum syrup

1/4 cup water

1 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon butter

Popped popcorn (half gallon)

Butter for your hands and for rubbing on pan

Directions:

- In a large saucepan, combine sugar, sorghum syrup, water, salt, and butter. Cook to the hard ball stage (about 250° on candy thermometer), stirring occasionally.

-

- Remove from heat. Working quickly, stir in popped corn (a big wooden spoon comes in handy) and turn into a buttered pan. (If the pan isn’t buttered, the rapidly cooling mixture will stick to it.) With buttered hands, shape quickly into balls and place on waxed paper to cool.

Makes about 6 popcorn balls

***

Hunting Ginseng and Elderberry Wine

In my teen years, before I got my driver’s license, large parts of my summers were spent in the woods with Grandma and 17 dogs. Honestly, I don’t know where all those dogs came from. I had two or three dogs, and Grandma had two or three. Each day after she fed Grandpa his lunch, we stuck a sandwich in a bread sack, grabbed our short hoes, and headed to the woods. Along the way we picked up dogs that seemed to appear out of nowhere. It was a joyous pack, tails wagging and happy barking. Anyone could have heard us coming for miles.

Grandma and I were hunting ginseng. Ginseng was prized in Asia, and dried roots sold for 30 to 40 dollars per pound. Hunting the wild variety was still legal then but is now highly regulated. The plants were endangered at one point.

We would hunt ginseng in the woods along Panther Creek. It’s a difficult plant to find, because it looks a lot like several other plants. On top of that it always seems to grow in difficult spots. Its roots like to grow under rocks and are often entwined with tree roots. But finding it was most of the fun. Despite her failing eyesight, Grandma always found more than I did.

One summer day we emerged from the woods. The elderberry bushes at the edge of the fields were loaded with berries. Grandma said she thought she’d like to make some elderberry wine, so we headed home for buckets. It took quite a lot of elderberries to make a gallon of wine, and I wasn’t old enough to drink, but I was still interested in the process. We got the berries back to the kitchen, rinsed all the bugs out of them, and Grandma set to work. If I recall correctly, she ended with only two gallon jugs of wine, even though we had five-gallon buckets full of berries.

That fall I asked about the wine and Grandma pulled a jug out from under the dining room sideboard. It looked very dark, almost black. She poured me a taste into a cup, and I have to confess I didn’t like it. You have to remember I was perhaps 15 and had never tasted alcohol. I still preferred my juice natural, and that stuff was strong. I might appreciate it more today.

I cherished those hot summer days in the shaded woods. We wandered over hills and along the creeks for hours, with dogs all around. If we couldn’t find ginseng, we’d sit under a tree and break open a fruit jar of water. One day we had climbed halfway up a large hill in the woods. Grandma said, “Let’s sit here by this hickory bush and rest a spell.”

We rested a bit and then started to get up. Grandma looked down and laughed. “Looka here,” she said. “That ain’t no hickory bush. It’s ginseng!” And she was right. We had not recognized it because it was so much larger than the ginseng plants we usually saw. She laughed about that for years.

The air always had a fresh, earthy smell to it along the creek bottoms. Birds sang themselves silly along Panther Creek. There were flashes of red as the cardinals darted from bush to bush in the shade of enormous sycamores. Sometimes we sat and listened to them. Sitting and resting with her on those shady hillsides were some of the few times I ever saw her truly relaxed. Grandma often brought up some story from her past and shared it with me. I realize now that I came home with more than just ginseng roots.

Gola’s Homemade Elderberry Wine

Ingredients:

5 pound bucket of elderberries

5 pounds sugar

1 lemon

1 large box raisins

1 packet yeast

Directions:

- Remove berries from the stalk. A large fork helps, for the berries will stain your hands. Prepare to get red all over everything.

- After removing berries from the stalk—and cleaning out any insects you might find—put berries only (no stems) into a bucket and pour at least a gallon of boiling water over them.

- Mash the elderberries; then add the raisins. Cover with cheesecloth and leave it in a dark place for three or four days.

- Strain the juice through cheesecloth into another bucket. Stir in the sugar until it dissolves. Add the yeast and lemon juice and leave it for an additional three or four days.

- At this point grandma strained it again. This time through a funnel into gallon glass jugs, which she stoppered with a clean rag. Then she left it all summer and into the fall. It was at least five months total.

- Sometime in the late fall, when the bright red maple trees had lost their leaves, the juice had turned to wine. I only got to taste it once; I was not considered old enough to drink. It was tart, fruity, and delicious. And it had a kick! Grandma also made wine from grapes, which she left to ferment for an entire year before drinking. I doubt many in the family even knew she had it stashed away. But I did.

***

The “ginseng years” came to an end, of course. Before long I was driving, and then moving away to college. I visited whenever I could, but Grandma and Grandpa had sold the farm and moved to town. And though Grandma always had a vegetable garden and lots of flowers at her new home near Barkley Lake, it just wasn’t the same.

I moved to Virginia after college, then Atlanta. I got home whenever I could, and of course I always visited my grandparents. During one sad month–December, 1978–both of my grandfathers passed away. I moved back to Kentucky for good in 1992.

Grandma died on the same day as Rose Kennedy, on January 22, 1995. She was 89. All 12 of her children were reunited for the funeral, along with dozens of grandchildren and great-grandchildren. As I sat watching hundreds of people file in and out of the funeral home I couldn’t help but think, “It’s not just the Kennedys–Lyon County has lost a matriarch too.”

In the years since her death I have reflected much on all I learned from Grandma Kingston. I was fortunate to have spent as much time as I did with her and Grandpa. During the 1970’s one of my favorite television shows was “The Waltons”, perhaps because it all seemed so familiar. I’m not being sentimental at all when I say that our country lives in Kentucky were similar in many ways to that famous TV family. The Kingston and Hammons family did the same things that other families did to survive the wars, depression, and changing times.

My grandparents were perhaps more uniquely equipped to survive than anyone I know today. They taught me the value of having land–how important it is to be able to grow food, raise farm animals, and do all the other things that create independence. They did all of that while raising a family and keeping them close. I admire them both so much to this day, and of course I miss them. Grandma and Grandpa Kingston are buried beside one another in the cemetery at Macedonia Baptist Church. It’s a beautiful spot on a hill overlooking Panther Creek. They are home.

***

Part Two – Esther

Though my grandmothers were similar in some ways, they differed in many others. Whenever I think of Grandma Kingston I immediately recall a woman with the greenest thumb imaginable, a woman whose kitchen skills were superb, and a woman who exhibited tireless energy and creative resourcefulness.

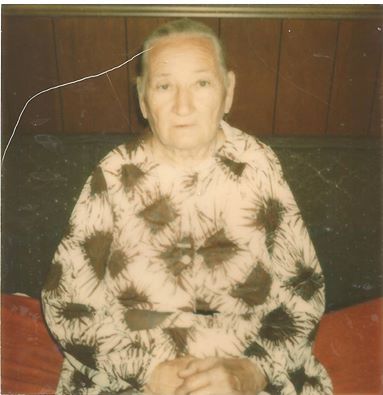

Whenever I recall my Grandma Hammons, my heart fills with the longing one has for a mother. She was kind, loving, patient, and most of all, spiritual. That she lived in virtual poverty for most of her life seemed not to matter to her. If anything it endeared her loved ones to her even more. She survived with little and did it with grace. She endured unimaginable grief over the loss of two children, yet her faith remained as strong as any fortress. The overall impression she gave everyone (even those outside the family) was of goodness. I have heard it many times in my life. When people spoke of her they inevitably said, “Esther Hammons is a good woman.”

Esther Scott was born on Christmas Day, 1902. It was Thursday. The 20th Century—a hundred years of marvels and progress—was only getting started. The Wright Brothers would fly the first successful airplane during Grandma Esther’s first year. The first movie theater opened in Los Angeles. Texaco was formed, and Denmark became the first country to use fingerprinting to identify criminals. Teddy Roosevelt became the first president to ride in a car. Unemployment was an incredibly low 3.7%. The country was optimistic.

Esther lived with her parents, Willie “Teddy” Scott and Florence Barrett Scott, in what is now referred to as “Old” Eddyville, Kentucky, on the Cumberland River. (When Grandma was 58 the town was relocated away from the banks of the river, as the Tennessee Valley Authority completed the Barkley Dam. The new Lake Barkley would flood the original location of Eddyville. “New” Eddyville is located a few miles from the original location.)

Esther had three brothers and one sister. Her dad, Willie, ran the ferry across the Cumberland River at Old Eddyville. They lived near downtown, not far from Kentucky State Penitentiary (KSP). KSP sits on a hill overlooking the river and town, and was not relocated.

I don’t know as much as I would like about Esther’s childhood. She tried to tell me more on a few occasions. (More on that later.) I know that she got up one morning as a child and told her mother that she had dreamed the house burned. That very night the house caught fire and burned. Esther’s brother, Howard, ran into the house to get his shoes and had to be rescued.

When Esther turned eight, Mother Teresa was born; and Mark Twain died. The American Boy Scouts were founded, and Kellogg’s put their first-ever prize in a box of Corn Flakes. The Scotts lived in a comfortable home. Esther was a bit of a homebody. Her mother, Florence, kept her close. Florence was a very religious woman. The family often attended the Eddyville Baptist Church.

Grandma was 12 when World War I began. The world’s first traffic lights were installed that year in Cleveland. The Boston Braves (yes, Boston) won the World Series, and “Old Rosebud” won the Kentucky Derby.

Esther turned 18 in 1920. By all accounts it was an historical year. Women in the United States were given the right to vote. The Prohibition Act went into force, and the number of bootleggers exploded. (Years later, bootlegging would become a dirty little open secret in Eddyville.) Silver reached a record $1.37 an ounce, and a New York Times editorial reported that rockets would never be able to fly. Walt Disney got a job making a whopping $40 per week. The first radio station began broadcasting, and the League of Nations was formed. An earthquake registering 8.5 hit China, killing an unimaginable 200,000 people. What a year to turn 18!

Esther met Calvin Hammons in 1921, and they married shortly afterward. I know little of their courtship except that they attended “picture shows” in downtown Eddyville. All the movies were silent.

The couple built a small clapboard house on Pea Ridge, the area on the hill above and behind Eddyville. Though they later built a concrete block home on the same property, they never really lived anywhere but in that small ramshackle house.

There was no electricity, no plumbing, none of the other modern conveniences we have come to expect. Water was drawn from a cistern. The house was heated by wood or coal. The kitchen had a wood stove for cooking, which also kept water hot for dishwashing and bathing. (It summer it was often too hot to light the wood stove, so they placed pans of water in the sun to heat.)

There was an icebox in an unheated back room, away from the stove. The ice man delivered the huge blocks weekly. The children were constantly reminded not to open the icebox door, lest it melt between deliveries. Ice was an expense.

Grandma gave birth to eight children, six boys and two girls. One boy, Leon, died of pneumonia at six months of age. My mother, Mary Lou, was Grandma’s eighth and last child, which meant she was the baby in the family.

Cemetery Picnics and Blackberry Cobbler

My mother’s earliest memory is of two women who came to the house. They enrolled her in the “cradle roll” from the Baptist church. When Mom started school she walked with friends down Pea Ridge hill to the Eddyville School. At lunch time they went up the hill and met Grandma at the Eddyville Cemetery. She would bring biscuits, bacon, and beans for lunch. It was like a picnic.

Grandma adored apples. “Get ready, we are going down to the bottoms,” she would say to the kids. They went down to Mrs. Martin’s land, where the trees were full of large June apples. For some reason no one picked them, so they hauled as many home as they could and cooked them.

Like most people Grandma also loved wild blackberries. They grew profusely along Pea Ridge Road and in the sunny bottoms. Mom liked to go berry picking with Grandma but was terrified of snakes. Sometimes they sold the berries to get money for Mom’s school clothes. Other times, Grandma used the berries to make her amazing jams, jellies, and cobblers.

If you have never had a “made from scratch” cobbler, made with wild blackberries and fresh-churned butter, and cooked in a wood stove–well, I kind of feel sorry for you. There is nothing quite like it. Hot, sweet, purple juices bubble up over crunchy buttery crust and fill the kitchen with the most mouth-watering aromas imaginable.

Esther’s Wild Blackberry Cobbler

Ingredients:

½ gallon (4 pints) of fresh-picked wild blackberries

2 cups granulated sugar

1 tablespoon corn starch

1 cup flour

½ teaspoon baking powder

¾ cup milk

1 stick butter

Directions:

- In a large pot combine washed and drained blackberries and 1 cup of sugar. Heat until berries begin to bubble.

- Remove about a cup of the blackberry juice and gradually stir in the corn starch until there are no lumps. Add the cup of juice with cornstarch back into the berries and stir well.

- Remove berries from heat and set aside. Make the topping by mixing 1 cup of sugar, 1 stick of melted butter, 1 cup of flour, ¾ cup of milk, and ½ teaspoon baking powder. Note that batter should just be thin enough to pour—not watery. (Alternately, you can make the biscuit recipe, roll out the dough until it’s ¼ inch thick, and place it directly on the berries in the baking dish.)

- Pour berries into a baking dish or pan. Pour the thick topping batter evenly over berries.

Add additional small pieces of butter to topping and sprinkle sugar over all. (This will give the batter a delicious buttery crunch.)

- Bake at 350 degrees if not using a wood stove. It takes about 40 minutes at 350, sometimes less in a wood stove. Topping should be lightly brown and crusty with berries bubbling out in spots. Serve warm, preferably with a scoop of vanilla ice cream.

Oh my. Nothing beats wild blackberry cobbler. Wild blackberries may not be as large and sweet as cultivated varieties, but they have much more flavor when baked. The mouth-watering smell will permeate your kitchen and beyond.

***

A Two-Inch Thorn and Boiled Frosting

It sounds like a cliché of the south, but most children ran barefoot all summer. (I did so myself as a child, even though we certainly could afford shoes.) Mom once ran a huge thorn two inches into her foot, and had to go to the doctor. She thought it was the grandest thing that she got to go to doctor, which was a rare thing. Grandma always laughed about it, and how Mom “put on”. But Mom was the baby after all, and Grandma petted her by making a chocolate covered cake in the wood stove.

Now a word about Grandma Esther’s cakes, which were not exactly pretty, but were so delicious they never had the chance to grow stale. Grandma kept chickens, of course, and gathered her eggs fresh daily. Because they were free range chickens, the eggs were rich with dark yellow yolks. They help to make the most amazing cakes. Fresh-churned butter added extra richness. And then there was the boiled chocolate frosting.

Boiled chocolate frosting is a simple topping with only a few ingredients. There’s no sour cream, cream cheese, chocolate shavings, or other ingredients we have come to expect today. Just butter, cocoa powder, milk, sugar, and vanilla, but oh—when boiled and poured over a wood stove cake—well, my mouth is watering as we speak.

Grandma poured the cake batter into a large cast iron skillet. When it came out of the wood stove the cake was brown and crusty on the edges, and a rich yellow inside. She left it to cool in the skillet while she made the boiled frosting, which she poured hot over the cake. After a few minutes the frosting cooled and hardened slightly. Then it’s time to eat.

Esther’s Boiled Chocolate Frosting

Ingredients:

1 stick butter

½ cup cocoa powder

1 cup sweet milk (whole milk)

2 cups sugar

1 teaspoon vanilla

Directions:

- Place all ingredients into a heavy pot. (Grandma used cast iron.) Place on medium heat, and stir until everything is melted and mixed together.

- Boil and stir until a teaspoon of frosting dropped in a glass of cold water becomes a ball that holds together.

- Remove from heat, stir vigorously with a wooden spoon for a minute, then pour immediately over the cooled iron skillet of yellow cake. Frosting can be a bit firm when completely cooled—though it rarely lasted that long at Grandma’s.

Delicious!

***

Convicts and Homemade Soap

My mother recalls that hard times lasted for most of her childhood. She was born in the middle of the depression, and soon afterwards World War II began. During the war many goods were rationed. The Hammons family had chickens and other livestock. There was always a garden. But other necessities, from gasoline to cooking oil, were hard to come by. Grandpa Hammons would bring in sacks of grapefruit when he could. Grandma kept used coffee grounds and mixed them with fresh coffee, to make it last as long as possible.

Fortunately, Grandma was never ill. She was a large woman, what we today call “big-boned,” though the word “obese” did not fit her. Her face was broad, with kind eyes. She had very long, thick gray hair that was always kept in a bun on the back of her head. She had a habit of sticking her tongue out about a quarter inch when she was concentrating. I have on occasion caught myself doing the very same thing.

Grandma’s hands, big and strong, scrubbed the laundry on a washboard. She used big blocks of soap she made herself and added bluing to whiten the sheets. Laundry was hung on a clothesline to dry. We played hide ‘n seek among the fragrant sheets, swaying in the breeze. Sometimes clothing disappeared from the clothesline. When a convict escaped from nearby Kentucky State Penitentiary, they stole the first clothing they happened upon. Once, when I was watching her hang the laundry, she was reminded of something that had happened many years before.

Grandma and Grandpa usually went to bed with the chickens. With no electricity for a fan in summer, they lay on top of the covers in their respective beds. Sometimes a stray breeze would meander in from the screen door at their feet—or whisper through the window screen by Grandma’s bed to rustle her rose-patterned plastic curtains.

On this particular evening a neighbor from up the hill walked down to tell them that a dangerous convict had escaped from the prison. News of escapees always rattled everyone on Pea Ridge.

To Grandma “dangerous convict” meant “rapist” and to Grandpa it meant “murderer.” Escapees couldn’t swim across the river in front of the prison, where the current was swift and strong eddies had given Eddyville its name. Convicts generally headed up the heavily-wooded hill behind the prison. Grandma and Grandpa lived in one of the few homes in that direction, so they were alarmed at the news.

Grandma, a fierce Christian warrior, began to pray. Grandpa (it was generally agreed) was probably the biggest “fraidy-cat” in the county. (Think of Don Knotts as Barney Fife and you pretty much get the idea.) After the neighbor left he double-checked the lock on the screen door.

Convict or no convict, it was too hot to close the wooden door. The fire in the nearby wood stove had barely died down. Heat radiated the short distance into the bedroom. It was suffocating, yet before long they were both asleep. Grandma’s deep, chesty snore was answered across the room by Grandpa’s more nasal whine. They were like two bull frogs calling across a pond. With no moon and no lights, the room was very dark.

A few hours passed, when suddenly Grandpa bolted awake. The screen door was rattling. There was no wind, so something had to be shaking it. He lay frozen for a minute and it rattled again.

“Who’s there?” he called out. No answer, but the door stopped rattling.

Grandma woke when he called out, and said, “What is it, Calvin?”

“I heard someone at the door,” Grandpa whispered back.

They lay silent for a minute, and Grandpa reached under the bed for his shotgun. Though he didn’t take his eyes off the screen door, it was so dark he couldn’t see who might be standing there.

“I have a gun!” he yelled. No one answered. Then the door rattled again, louder than ever. The little hook jangled in its eye, threatening to come unlocked.

Grandpa sat up in the bed and raised his shotgun. “I said I have got a gun and I’m gonna shoot!” Again, the door stopped rattling but no one answered. They waited. For a full minute there was no sound at all. Sweat broke out on Grandpa’s face–his hands were wet on the gun. Grandma clutched her big Bible and murmured a prayer.

Suddenly the door shook louder than ever, and Grandpa fired the shotgun, “Boom!” One blast cut through the middle of the screen. They heard a small thud, then nothing. Grandma, ears ringing, fumbled for a match to light the kerosene lamp. Grandpa sat clutching the shotgun to his chest.

Grandma fumbled her way to the door and raised the lantern. All she could see was a big hole in the screen door. She unlocked it and peered out into the dark. At first she didn’t see anything. Then she looked down and said, “Aww.”

Lying on the stoop, blown nearly in two, was Grandma’s cat. It had apparently climbed the screen in an attempt to get back in. Blackie had gone courting a week before. His nights of romancing were now over.

“You killed Blackie,” said Grandma. “Oh,” said Grandpa, who was as fond of the cat as Grandma. His head drooped as he scooted the shotgun back under the bed.

“I know you didn’t mean to,” said Grandma. “What time is it?” Grandpa fished for his pocket watch in the britches hanging from the bed post. “It’s just past midnight.”

Grandma said, “That prisoner is probably long gone by now. I’ll leave the door like it is, hole and all.” Soon they were snoring again.

Esther’s Homemade Soap

Ingredients:

Hardwood ashes

Rainwater

Lard

Salt

Directions:

- Put hardwood ashes in rainwater and boil for an hour. (Don’t use aluminum pots, for the lye will burn right through them. And be careful not to splash the liquid on you or in your eyes. It’s quite caustic.)

- After the ashes settle to the bottom, drain off the liquid.

- Repeat process daily until you have enough liquid, and it has been boiled down to where an egg will float in it. Then it’s thick enough to continue.

- Add melted lard to the bubbling lye and continue boiling until it’s thick like cornmeal batter.

- If you want to make the soap into hard bars, stir in salt before you pour into your molds (if you have them.) You can always just pour the liquid into any flat, greased container. Grandma made sheets of soap about 2 inches thick, which she broke up into irregular shapes when it hardened. It was yellowish and had a strong odor, but could clean virtually anything.

*Note–I was amazed that grandma made soap from ashes and hog fat—two things I had always associated with stained clothing. It just didn’t seem possible somehow.

Both my grandmothers also used lye to make hominy out of dried corn. I didn’t pay enough attention to that process to accurately remember the recipe, but recipes can be found easily online. Making hominy is a time-consuming process. It usually takes several days to soak the dried corn until the husk and nib can be washed away. Though I love grits, unlike most of my family I never cared for hominy.

A Handkerchief of Pennies and Snow Cream