The following was taken from a tape my father, Russell Kingston, made for me several years ago. He shares some of his experiences growing up, as well as his time as a prisoner of war in North Korea. I would like to point out a couple of things up front: One, these are not all of his P.O.W. stories. Some are just too disturbing to include here. There are times I wish I hadn’t heard them myself. Two, Dad jumps around a lot in his telling. I could tell when listening to the tapes that he became emotional and had to switch back to the farm years, or something else more comforting. The words are his, just as he spoke them, with no changes.

I’m happy to add that, as of this writing, Dad is very much alive and doing well. –Wade Kingston

This is Russell Kingston. I’m gonna tell a few things of my life history. I was born 12/21/31 to John and Gola McKinney Kingston. I have lived on a farm all of my life, my childhood, and when I became a teenager I decided I would go in the army, which I did. I joined the army May 11, 1950, went to Ft. Knox, taken seven or eight or ten weeks training and I was sent home for 18 days delay in route. I went to Chicago, transferred from that train to another and went to Seattle, Washington and stayed there for a day or a day and a half, caught a plane and went to Tokyo, Japan. I spent one afternoon, one night and part of one morning in Tokyo. Caught a train and went to Sasebo (Nagasaki), Japan. From Sasebo I caught a ship which they said was Japan’s second-best ship and when I woke up the next morning I was in Pusan, South Korea and when we got off the ship, they told us to take a look at our enemy, which there were prisoners lined up on the railroad as far as you could see—North Koreans, so they issued us more ammunition and told us to go to our outfits. I asked them where was I going and they said “You are going to the First Cavalry, Eight Regiment, K Company,” and I said, “Where is it?” and they said “Somewhere between here and the 38th Parallel.” I said, “How will I get there?” And this officer said, “Well, soldier you have two feet don’t you?” I said, “Yes, sir.” And he said, “Well, use them.”

So, I hitchhiked—caught rides on sea ration trucks, water trucks, you name it and I rode it. And two days later I was in my company, which I went into K Company, First Cavalry, 8th Regiment. I went into the company and we started our push north. I went on in to Taku, and I went to Seoul, and I was in Pyongyang, which is the capital of North Korea.

And when we was in Pyongyang, they told us to turn our ammunition in, that we were going to Japan to pull a parade on Thanksgiving Day for General Douglas MacArthur. So everybody was thrilled, we turned our ammunition in, and a day or two later they hollered for us to fall out, that there had been a change in plans, that the Chinese had come into the army. So then we started our push north and I was in Unsung (Anson?), North Korea. On the night of the second, 1950 in November the Chinese came across and attacked the 8th army and from there we retreated back…I don’t know, maybe a mile or two and we dug in and made us a perimeter and we stayed as long as we could stay. We had to retreat and when we retreated we were on our own. Every man was for himself so there was about 300 of us, I guess, so we took to the mountains.

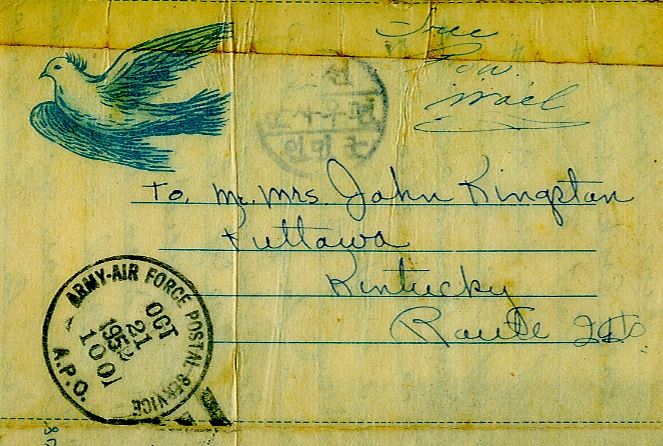

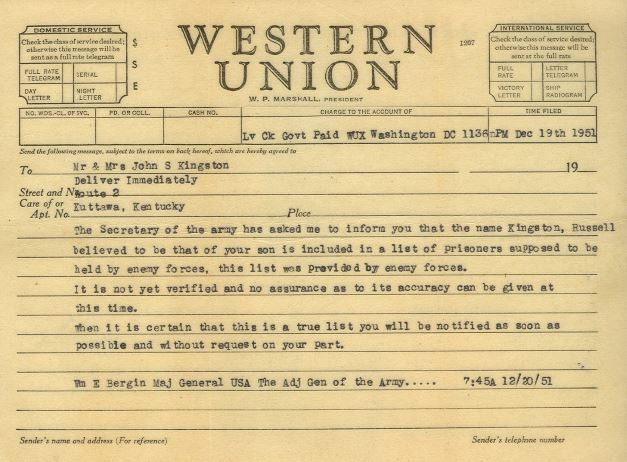

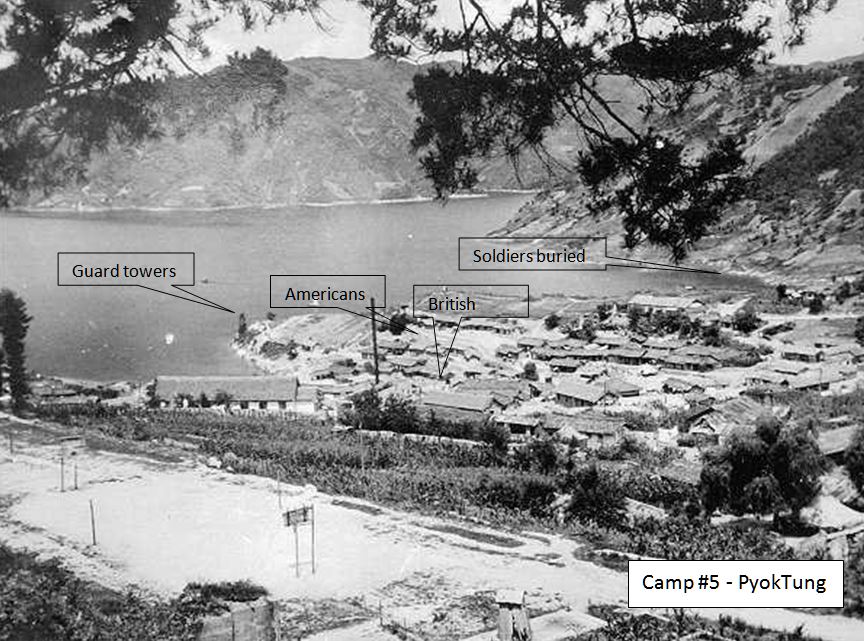

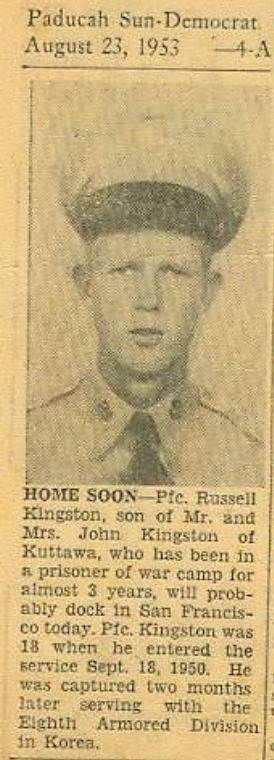

The next morning myself and four others, we started at a different direction and we stayed behind the enemy lines for 16 days and on the 18th of November, 1950 the Chinese and the North Koreans overrun the building we were in and I was captured, I was taken prisoner of war. From there I was marched during the night, we’d march all night long, and then in the daytime they’d put us in old buildings without heat and when it came night again we would walk again. And I walked from the time I was captured until the day before Thanksgiving without a break. Then we went into Death Valley, which was full of soldiers. We stayed there until Dec. 25th of 1950 and we left there and we went into POW camp number 5, Pyoktong, North Korea, and as we started in the camp, the American planes started bombing and strafing the camp so we had to retreat back, we went back to the valley that we had just left. And then on January 25th, 1951 we went back into the same camp and they had put up the Red Cross signs and our planes would honor those signs, and then there in the camp is where I stayed the remaining time. I stayed there until Aug. 11th of 1953. In the meantime, while I was there I had malaria fever twice, I had my tonsils removed by the Chinese in a little makeshift hospital they had. I had one tooth pulled with no Novocaine and I won’t even say how many times I was forced labor and this, that and the other because I don’t know whether people would even believe if I done forced labor or not. Then in August 11th, 1953 they told us that we was gonna git to come home. During that time, before I come home, my mother heard from me. She got a letter from me that was sent through Peking, China. The letter that she got, from the time I left home until she got the letter was 16 months, and I got a letter from home and the time was 18 months.

I got mail pretty regular from home and I was allowed to write maybe once every month or every two months. Over there in the winter time it got 40 or 45 below zero and it would snow for two or three days and the snow would be waste-deep. You were stranded, you pretty much had to stay in your rooms during that time because there was so much snow that you couldn’t get around with no more clothes and the kind of shoes we had to wear. They taken our army clothes away from us and gave us prison blue. They told us we was coming home, they sent the sick and wounded first, and then on Aug. 11 on 1953 I was released at Freedom Village, South Korea and from there I got on a ship at Inchon, South Korea and I was transported to California. From California I was put on a plane and flew to Louisville, Ky. where I met my mother and my dad and my youngest brother and my youngest sister. From there I came home and I had a month at home. After the month was up I went back to Camp Breckinridge, Ky. and got discharged. In the meantime, the second day I was at home I went to Eddyville with a good friend of mine and we went in this restaurant to get us a sandwich or something. There was someone standing at the jukebox and I asked my buddy, “Who in the world is that good-looking thing standing over there by the jukebox?” And he told me it was Mary Lou Hammons and I said, “Well, I want to talk to her.” So I went over and I started talking to her and she was a little shy at first. And then I pulled out some change and told her to play the jukebox and she says, “What do you want to hear?” And I says, “Oh, you just play anything that you want.” So I got to drive her home and made a date with her for the next night. And then I bought me an automobile and I started seeing her every night, every day after school…she was still in school. And I went to Indiana and went to work in the latter part of that month and I proposed to her and she accepted. So I went on back to Indiana and worked a couple of weeks and come home and we married. We have four children, we have three boys and a girl and they are all wonderful. I have two grandchildren. One is twenty and one is thirteen (when tape was made). When I come back from Indianapolis, Ind. my job went berserk and I came back down here in 1954 or early 1955 and I went to work for an oil company…Ashland Oil. I stayed with them for 38 ½ years, I retired from the Teamster’s Union. Now I’m on social security, Teamster’s Union and I get a small disability check.

I’m going back now into Korea. I told you some of the good times I had, which I really enjoyed, so now I’m going to tell you about some of the bad times I had in Korea. Me and a boy, well not a boy, he was a soldier from Wisconsin, we went to the lake. The boat that came in had soybeans on it, so we decided we wanted soybeans so we tied our pant legs with string and we filled our pant legs with soybeans. On the way back to our room there was a fellow in front of us who had done the same thing and as we walked by the Chinese guard one of his strings broke or came untied and he got to losing soybeans. Well, the Chinese caught him, caught me and caught my buddy. He taken us over to the Chinese…what they call “Chinese breakdown” and put our feet in a tub and he cut the strings and let those beans fall into a tub. Then after that they throwed us in an old building and then put us out one at a time with the Turks–we had a bunch of Turks in our camp. They put us out there one at a time, they put my buddy out there pulling the end of an old crosscut saw, sawing wood until he give out and he came back inside and the Chinese put me out there. I was so weak and had lost so much weight that I didn’t pull the saw very long. I told him, “I just cannot pull the saw,” as sore and as weak and as hungry and everything as I was, “I cannot do it.” So they taken us up the hill, I thought maybe we was taking the roundabout way to our company but they took us up the hill and put us in an old bank vault and we stayed in there a week or ten days. They let us out, and we went on back to our company and then, when I told you at first that I had had a tooth pulled without any Novocaine, the reason I had that tooth pulled—one GI hit me for no apparent reason, in the mouth and knocked that tooth out and loosened another one severely. I was standing in my room—I had an old guitar string and I had it wrapped around that tooth and I was trying to pull it with tears in my eyes—and I couldn’t pull it.

My Chinese company commander, he came down to where I was and he stopped and he seen what was going on and got close to me, and he showed me his gold teeth and silver teeth, you know, and when he did, well that just upset me and I hit him just as hard as I could pop him, right in the mouth. It wasn’t too awful hard because I was weak and underfed and first one thing and then another. So he started hollering in that Chinese lingo, and within a minute or a minute and a half there was four or five armed guards had their guns poked in my belly and I thought they was going to shoot me. That’s when they took me to the little clinic that they had and pulled my tooth without any Novocaine, and the doctor said, “Go on, go on.” So I went outside and I thought I would go back to my company, but the guard that taken me to get the tooth pulled, he was still there. He got me by the arm and motioned me to go another way. When he did I went back to the bank vault again. I don’t know how many days I stayed in there then…probably 8 or 10 days. The only thing I got while I was in there was water…once a day. The Chinese would open the door and hand in a helmet, a helmet liner full of water to myself and the other guys that was in there. During that time I was in there, I got so weak that I couldn’t hardly walk. They finally let us out and I made it back down to my company.

Then in the spring of the year we started on details. They would take us out of the camp about two miles, three miles into this creek bed—dry creek bed, no water. We would pick up rocks and they would force you to get a rock as big as you could get. If they got one that was small, they would pick up one or show you one to pick up, so I learned real quick to get a flat rock, as big as I could get, but let it be flat and not too much weight. We would carry those rocks back into camp, lay them in a pile, and the Chinese built a theater with the rocks and what time we was there we was allowed to go see some movies and the Chinese would have those Chinese women, would come in—they looked just like dolls—and they would put on a show for us during the Summer. In the winter-time when it would get cold and the lake would freeze over we would go on wood detail. We would go a mile or a mile and a half onto the lake and then go up into the mountains and break limbs. We could only get dead wood; we couldn’t get any green wood whatsoever. We’d go up and ride down the dead trees and bring them back into the camp for our heat.

Our food consisted of rice—brown rice—once a day, sometimes once in two or three days. When we were first captured we didn’t get any rice, we didn’t get anything for several days. The only thing we would get would be the water that we would get off of icicles that was formed on the hillside and on the rock cliffs that we had to go by. In the summertime when we wasn’t working we dug a football field back into the mountain.

What time we wasn’t working we had recreation. We had the Yellow River, which joins North Korea, China and Russia—they all join in one point. In 1951, the spring of 1951, I was in squad 14, so when I was captured they taken my billfold with what belongings I had in it, so in the spring of ’51 they gave me my billfold back and told me that I was going home. They put us on a boat and took us downstream to Anson dam, a big dam that was built by the Japanese when they fought Korea back several years ago, and taken all their timber. They would float the timber down to the dam, load it with a crane onto railroad cars, and ship it to Japan. We went down there and we was going home. We got down and we stayed in this one building for about two days. So they took us out of this building and marched us around a curve to a railroad station and there wasn’t no train there for us to get on, so they brought us back, took us back up the mountain, put us back on the same boat and brought us back into Camp 5 again. Everybody was downhearted, you know, because they didn’t get to come home but finally they just forgot all about it.

Then on another occasion I was standing, I don’t know if it was in ’51 or ’52, but anyway I was standing on the outside of my room and the jets were coming over, the American jets, they were in the air and they were having dogfights with the Russian migs. The Russians came to North Korea and China—a bunch of planes—to fight the Americans.

I was standing there watching the dogfights and there was about 50 GIs coming through the perimeter where I was standing and when the last man went by, there was a North Korean soldier in line marching them, but there was several guards. He got me by the shoulder and shoved me into the line. So, I didn’t think nothing, I thought it was a wood detail or a water detail; we carried water a lot for the kitchen. So, they taken us over the mountain behind our kitchen, put us on a boat, and they never did back the boat out—they just, the Korean that was operating the boat with a big paddle behind, he just took a big pole and he shoved it about a hundred yards up in a ravine. When he went up there and went aground as far as he could go, the North Korean soldiers got off the boat, got on the bank, and uh loaded their weapons. And I said to myself, “Lord, this is it.” I figured they was going to shoot every one of us on the boat. And the Chinese got to hollering and carrying on and talking back and forth to them, so they uncocked their guns and unloaded their guns and got back on the boat and the North Korean he backed the boat back up to where we had got on it, and we got back on land and went over into our camp. And that happened one more time, but it happened in a different direction. We were marched out of camp to a mountain site, and I was taken out of the camp twice to be shot—but one time I was taken out to be released and there wasn’t any train. I found out later that if there had been a train there I wasn’t really going to be released. I was going to a salt mine in Russia. And, uh, that was what was told because there was—one company that was in my camp was the black company, and there were loaded onto the trucks (I didn’t know this until I came home. We have our POW reunions every year and one of the black boys told me that when they left that camp the Chinese blindfolded every one of them and when they got off the truck they were at a salt mine. I don’t know what country it was in but they were gone from the camp I was in for a year or a year and a half.) A few days before I was released all the black boys came back to the camp that they had originated from. I didn’t get to talk to them then, but I found all this out at one of the reunions.

In the camp that I was in we would have lectures. Uh, the Chinese had an English-speaking Chinese, he was old and had glasses and we called him “Old Four Eyes.” And they would have lectures but not feed us for four or five days before, and what they would do is try to break us down. Get us to admit stuff. And, uh, wouldn’t nobody do it. Then they’d get a little better, be good to us for a while, then start them lectures back up again. And one day they was having them lectures and I had on an old cotton-padded suit that they gave us, and I had—I don’t know smoked some cigarettes out of some kind of old tobacco—and I had burned a hole in ‘em and you could see the cotton, so I pulled the cotton out of my uniform and stuck it in my ears, and uh, this Chinese come by and he reached up and pulled that cotton out of my ears and he said, “What’s matter, you don’t want know truth?” I told him, “No, I don’t want to hear it.” So, he took me up to the front and made me stand there while the camp commander finished his talk to us and when they got through, and the other GI’s rode me for days, saying, “What’s the matter? You don’t want to know the truth?” But I didn’t care.

And one day in the camp, why just above where my room was, was the Chinese headquarters. And, uh, they had a little old rooster, little red rooster, and they had a string tied around that rooster’s leg and tied to a stob. And they’d throw out rice to that rooster and he’d eat it. So, a real good buddy of mine, Freddy Gray from South Carolina, he said, “Kingston, the first time that rooster crows he’s our meat.” And I said, “What do you mean?” And he said, “I’ll show you. You wait till it crows.” Well, about three or four months went on and there one morning he said, “Did you hear that?” And I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Let’s go.” Well, that little old rooster didn’t make a full crow, he made like a half a crow and we eased up on the side of the hill where he was and I leaned over and Freddy got on my back and leaned over and got a hold of that string that the rooster was tied to. And he was just scootin’ that rooster closer and closer to where he got close enough he could grab him around the neck and he shoved him under his coat and we took off down to the lake. Dark as it could be. So, we went down there and while he was skinning the rooster I was down on my hands and knees digging a hole in the sand to put the feathers and the insides of the chicken in it. So, we got it dressed and he shook it real good in the lake water and went back up to the room. The next day we was to go on wood detail out of town, so we had a fire in our little fireplace, so we put that rooster in a steel helmet and put water in it and put him up on those coals and when we come back, why that was some of the best food I had while I was in Korea.

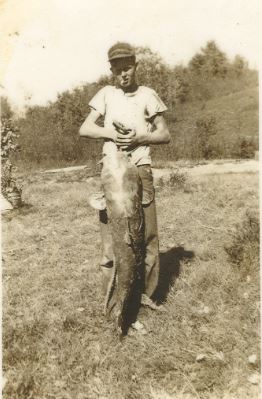

And fish—I would fish in the camp and I think I caught the biggest fish ever caught in the camp, but it was only about 14 inches long, about big around as a pint jar, I don’t know what kind it was, but it eat good. And we wasn’t allowed in that camp to go anywhere without a pass. My first sergeant on the front lines when I joined the company, his name was Brassfield. He had 18 ½ years service when he was captured. And I went up in his company—I got a pass—and I went up there to see him and he was poorly, real sick, down. Well, about a month of two passed and I went up to see him again was told he had died. When he died he had 20 ½ years service, and he had gave me his address and a picture of his daughter. They lived somewhere in Ohio. And when I come home from Korea I took the address and put his daughter’s picture in an envelope to them in Ohio and told her that I was sorry and that he wouldn’t be coming home. It was hard to do, but I did it.

I need to get off this war stuff for a while and go back to when I was little.

Like I said I was born in ’31 and it came a flood. I remember my mother and we would go over on the next ridge from where we lived to where we could see the Cumberland River and there would be houses coming down the river, crashing into trees. I was small but I could remember and there would be dogs and cats, first one thing then another, on those roof tops.

I went to a little old country school which was about a mile or a mile and a half from where we lived on this hill, and uh, when the water would come up in fall or spring or whenever, we would have to get on a john boat and my dad or the neighbor would have to make two or three trips to and from one side of the bank to the other to send us to school. And we’d go to school and that afternoon it was the same thing all over to get home.

Then we moved from there to a place on Panther Creek and my mother’s brother—it was in ’41—he was being drafted into the army and he wanted us to stay where he lived and we did that, we stayed there and in the meantime my dad bought a farm that joins it and built a new home on it. We farmed both places, tobacco, corn, hay. Me and my two older brothers we did most of the work, which, there was seven boys in my family and five girls. Which, you don’t get too much out of girls on the farm except cooking the meals, and me and my two older brothers were the only ones old enough to do anything on the farm. All the younger boys could do was carry your water and get in your way half the time. I remember one time me and my oldest brother—I won’t tell you which one it is—we whipped one of my brothers that’s older than me. We whipped him real good and he got mad and he said, “Well, I’ll just go down Aunt Lizzie’s.” Which, it was about two miles down the road, and it was a raining. And the old farm my dad bought had an old stock barn on it and we kept our cattle and horses and first one thing then another on it and my brother says, “Russell, let’s go down to the barn.” And I said, “Alright.” So, we headed down to the barn and the old dog we had, had treed up in the woods and I said, “I’m gonna go see what the dog’s got.” Before I got up there where it was, why the old dog was scared. It would run forward, then run back, run forward, then run back. And I seen someone standing behind a tree and I told my brother, “Here’s Tony behind this tree up here.” And my brother said, “Catch him and we’ll whip him again.” And he headed up the hill and I was gaining on him and he went in the back side of this old house we hadn’t torn down yet, and he went in the back side and out through the front and jumped off the end of the old porch. I ran out behind him and my brother caught up and said “Where did he go?” And I said, “That wasn’t Tony. Look at these shoe prints. They have cleats on them. Tony don’t have shoes like that.” Come to find out whoever we was chasing ran on down the road and someone else got after him and he jumped in the river and swam over it. Come to find out he was an escaped convict and when he got to the other side of the river, why he turned himself in. He gave up and they took him back.

I’ll tell you a little more about Pyongyang. I was in Pyongyang, North Korea, and during the time they told us we was going back to Japan to pull a parade for McArthur. We was living it up. Resting, pulling guard, and first one thing and another. And Bob Hope came to Pyongyang and my first sergeant, Brassfield told me, “Kingston, we’re going to see Bob Hope tonight.” And I said, “What did you say?” And he said, “I said WE are going to see Bob Hope tonight.” And I asked him, I said, “Are you pregnant?” And he said, “What do you mean?” I said, “You said WE, and I’m not going to see Bob Hope.” And he said, well if you don’t want to see Bob Hope you go tell the guys on guard duty to get ready and go see Bob Hope and you pull their guard duty.” And I said, “Fine, I’ll do it.” And then he said, “And another thing, Kingston you will shave tomorrow.” So I said okay, which I was a little wooly and I hadn’t shaved in quite a while. So, the next day me and Riddle, my best friend there from Tennessee, why, we went out in town and this Korean woman had a big old kettle and she was roasting peanuts. And Riddle could speak some of that stuff and he said, “You give us some peanuts and I’ll bring you some rice back.” Well, she filled our field jacket pockets full, I guess there was a half gallon peanuts in each pocket, and we went back to camp and I was eating those peanuts, dipping my hand down in to the pockets. And Sergeant Brassfield, the one that told me I had to shave, he said, “Kingston, what are you eating?” I said, “Peanuts.” He said, “Give me some.” And I said, “Nuh uh.” And he said, “Give me some peanuts.” And I said, “Nuh, uh. You remember what you told me I was gonna have to do today?” He said, “Give me some peanuts. I don’t care whether you ever shave or not.” (Laughs)

And I had a real good sergeant that was the mess sergeant. We’d get through eating—whenever we was around a kitchen, cause most of the time we was on a march and not around a kitchen—and his name was La Strada, and he would give me a gallon can of peanut butter and a gallon can of jelly and two big G.I. spoons, and he would help me put the peanut butter and jelly together on a big biscuit. And he said, “You mix this up real good and holler for me.” So, I’d call him and those little Korean boys and girls and he’d put it on whatever they had, sometimes they just had their hands out and we put peanut butter and jelly on their hands, just whatever he could give them when he could. I didn’t care.

My sergeant, Brassfield, the morning we got hit—I’m just telling some of the things that happened in Korea, because to be truthful with you I marched and bummed rides and hitchhiked and rode tanks and artillery pieces and trucks and everything from Pusan, Korea all the way to the Yellow River. All the way through South Korea and North Korea. I went up through Tagu and Inchon and Pyongyang and all through the major towns. But the morning that we got hit, on the morning of the 2nd of December in 1950, my first sergeant, Brassfield, he was in front of me crawling through this rice paddy and I was behind him and my buddy Riddle was behind me. And the American tanks seen us at break of day and they seen us behind this dirt wall. And the guy on the tank he got to shooting and I could see the dirt fly up over his back, Sergeant Brassfield. And I said, “Sergeant, you need to get lower.” And he said, “Kingston, I’m as low as I can get.” Then he said, “Oh, they hit me.” So, we laid there a while and I said, “Just lay still and maybe they’ll quit shooting.” Well, it wasn’t long and the guns were all silent and the guys ahead of us had made a perimeter for the sick and wounded, and I told him, I said, “Sergeant you get up and you run toward that perimeter over there in the field. If you don’t make it me and Riddle will come by and put you into the compound.” Well, he got up and he was a pretty good size fella, I guess about 250 pounds, and he set out running and he liked, oh, 20 or 30 feet I guess getting to the dugout they had. Well, when he fell Riddle and myself we jumped up and we run and there was somebody shooting at us but they didn’t hit us, thank God. And as we went by Sergeant Brassfield I reached down and got a hold of one pant leg and Riddle got a hold of the other and we flipped him over into the compound where the other wounded guys was already at.

And then I went on over to the other side and I grabbed a shovel and started digging on a fox hole. And some guy came from out of nowhere and asked did I want him to help and I said “sure” and we got it down to about waist deep and I went down to get a shovel of dirt, then he’d go down for a shovel of dirt and there was—I don’t know if it was a bazooka round or a mortar round, I don’t know, I saw it, looked like it was about knee high–coming across the field had been fired from somewhere and I hollered at him and when I did he just stopped, he didn’t really know what was going on and I went into the hole and that round come on through and just as he made a throw of the dirt it caught him below the elbows on both hands and it just tore him in two from his chest up. It throwed his head and his arms and everything out on the bank and the concussion throwed me down into the hole and when I come to I got a hold of him and there wasn’t nothing but just waist down in the hole, and I got a hold of that part of his body and fished it out. And that’s when they hollered to retreat and I had to leave him like that. And I never knew who he was, what company he was with or whether he was second division or who he was. And then, that’s when we left the perimeter the Chinese were firing so heavy, and I thank the Lord for it, there were tracer bullets going between my legs, in between my armpits and beside my head, and they were hitting guys all around me and somehow I made it to the river bank without so much as a scratch.

When I got wounded, I got wounded before Sergeant Brassfield did; I got hit in the leg and in the side of the face at the same time. I had the shrapnel taken out of my face several years ago, but in my leg it never was taken out and sometimes I can feel it. But I had to have it removed from my face because it was giving me headaches.

In my company we had machine guns, we had mortars, we had bazookas and we had rifles. When I first went into the company they put me on a machine gun and carrying ammunition. I carried two boxes of ammunition for the machine gun. Well, we got a replacement in, and they had done told me that when we got a replacement in you can get off of carrying this ammunition. I said, “Sergeant, isn’t it about time for me to set that ammunition down?” And he said, “Yes, tell that other guy to carry the ammunition.” Well, later on that day they had me carrying mortar ammunition. I carried twelve rounds of sixty-millimeter mortar. And we’d go up and down them mountains and one day we started down the mountain and it was a long ways, and it wasn’t nothing but shale rock. And the guys would sit down on their feet and they would scoot all the way down that mountain. So I waited for them to get down and when they did, why I took my pack board off, which I had a case of mortar ammunition on it, and I sat down and said, “Look out, here I come!” Well, I went all the way down that mountain riding that case of mortar ammunition and my company commander, he told me, “You gotta be the craziest SOB I’ve ever seen in my life. What if that hadda blown up?” And I said, “Well, I wouldn’t have been able to tell you about it.”

It wasn’t long then until we got another replacement and I got off that. The sergeant gave me, believe it or not, gave me two bazooka rounds. One of them was in a tin, you opened it like you used to open coffee, and the other one had electrician wire tied to it and I told him, “Sergeant, there ain’t no way I can carry two rounds of bazooka ammunition, plus my rifle, plus my ammunition and my extra clothes and this, that, and the other. And he said, “Well, it’s up to you to carry it.” So, I would get this little old Korean boy—maybe 15 years old or younger—to help me carry it and the sergeant said that whatever I did I should feed that boy at the end of the day. And I did. At the end of the day I’d lay out whatever C-rations I had in a pile and told him to take it. And he’d pick ‘em up and shake ‘em. If it rattled he didn’t want it, because that would be cocoa or maybe an orange slice or crackers or matches. He didn’t want that. He would take anything that would not shake. So, he would take him a can or two and he would go home. The next morning—there was always kids around—I’d get me a new one and let him carry it for me. And we did that all the way until the morning we was hit. I don’t know where the little Korean boy went to that was helping me that morning.

For those 16 days we were behind enemy lines, there was myself and four other boys, and we’d take turns each night trying to make it back to the American lines. I would scout while the others slept during the day and I’d sit and watch the villages, the traffic going into the villages and the people going into the villages and out. And come late in the afternoon we would go down into the villages and raid what we could raid, get water or find food, this, that and the other. And I know we went down one afternoon and there was a Korean lady coming up from the village and we walked upon her before we knew what was going on, and she reached up, she had a big crock of water on top of her head, and she reached up and set down that crock and turned around and she screamed like a panther and she run about as fast as one down to the village. Well, we high-tailed it out of there and went back up on the mountain where we had been and it was my night to leave and I told the boys that we should go across the road, I said, “I’ve watched across that road all day and I haven’t seen any movement.” Well, we went down off the mountain and started off across this old cornfield and we got pretty close to the road and the Chinese heard us, and they knew it wasn’t their soldiers, and they got to hollering in Chinese, which I didn’t know what they was saying, and they got to jerking the bolts back on their rifles and I stopped and the boys stopped behind me and I told them to go back to where we come from and we’d meet there. So they said okay and they outrun me going back up through that cornfield. They sounded like a bunch of horses going back up through it. Well, I jumped in this ditch. I thought I was going the same way they was, and something reached and grabbed me around the waist and I went backwards. Well, I made another lunge and whoever it was pulled me back again. I thought it was a soldier so I went back with both elbows to knock him off me, and it wasn’t nothing. What it was, I had jumped in behind a root wad, and it was a big old root coming out of the bank of the ditch and I had hit that root and thought that somebody had grabbed me. After I figured out what it was I stepped up on the root and I went up into the mountain and I would stop and I’d say, “Riddle, where you at.” And he’d say, “Right here.” And I’d crawl another hundred feet toward the sound. And I’d say, “Riddle.” And he’d say, “I’m right here.” And we’d be further apart. And this went on and I realized he was crawling too and we was crawling past each other in the dark. So I said, “Riddle, you stay put and I’ll crawl to you.” And finally we all got back together on the side of that hill, and we was out there five days and on the 18th they got us and that’s when our march started north.

In Camp #5 I think it was, probably 1952, one spring day the boys was all playing on the parade field that we had dug back into the mountains and the Chinese came down there and told everybody to get off the field. Go to their rooms. And I was already at my room but I could see the parade field really good. And what I saw, I thought I saw, and it was, Mao Zedong, who was the Chinese leader at that time, and Joseph Stalin and they walked down through that parade field that we had dug into that mountain and turned around and walked out the same way they had walked in. And the Chinese told us who it was and confirmed what they were doing was making a survey of the camps. I told a lot of guys I saw them and they told me I couldn’t have, but the Chinese told us they were indeed there.

When I was in that camp In the meantime, while I was there (in the camp), I had malaria fever twice. I had my tonsils removed by the Chinese in a little makeshift hospital they had. I had one tooth pulled with no Novocaine, and I won’t even say how many times I was forced labor, this, that, and the other, because I don’t even know whether people would believe that I done forced labor or not.

When I had malaria for the second time, they carried me up to this little ole Chinese building. They left me in there three or four days. Then they gave me a little shot in the arm, which was–I don’t know–probably sugar water or something like that, I don’t know.

To show you some of the hardships, uh, it was early spring and it was still kinda cool. Well, I got to feeling better and I got up and I walked outside and the sun was shining on the side of this building. So, I walked over to the side where the sun was shining, and when I walked over to the side of the building there was a G.I. standing there with no clothes on whatsoever. And I said, “Buddy, what’s wrong with you?”

He said, “Well, I’m out here to pass a worm.”

I said, “What do you mean?”

He said, “Yeah, the doctor said I had a tapeworm and I came out here when the pain hit me. They gave me some medicine and told me to come out here when I had to go.”

So, I went on back in but later he passed the worm, and I had never seen one. And there were doctors out there with sticks stretching it out and measuring it. I guess it had to be about six or eight feet long. It looked to me like garter rubber, like women used to put in skirts and stuff.

Later on, I was so sick I couldn’t raise my head up. This little nurse came in, and she was young and a pretty thing. She went about giving shots to some of the other guys with malaria, and by next day a couple of them were dead.

Well, she came over to my bed and she had two needles. When she raised my arm she seen my watch.

I smiled–which I was so weak–and I said, “Would you like to have my watch?” And I gave it to her. I thought I was about to die anyway.

She put down the needle she was about to give me my shot with, and reached over and got a different needle and gave me a shot with it instead.

The next day I felt better, and was able to leave the hospital not long after. I never saw that nurse or my watch again.

But I’ve always wondered, “What was in that first needle?” And would I have died if she had given me that one instead? I don’t know.

And I told you earlier I had my tonsils removed in a little old clinic and they took me downtown to a Chinese doctor and I couldn’t even swallow water for a long time. Another buddy of mine they did him at the same time, and he got to coughing and carrying on and broke his loose and almost bled to death before they got him settled down. He finally got well and we both went back to camp at the same time.

One of the funny parts—we was in those rooms–it was probably ten feet square and you would lay down on your side with you heads against the wall and your feet would lap in the middle. And everybody lay on one side and if somebody against the wall—you didn’t have room to lay on your back, you had to lay on one side or the other—and when I went into this squad I was the last one to go in there and I was next to the door where all the cold air was. Well, believe me it’s the truth, I woke up one morning and the guy behind me was dead. So, we got him out of the room and put him with the rest of the dead guys out there, they died like flies. And then I finally got to get away from the door and a day or two later the guy next to the door died. So, that was one on each side of me that died within a week and I thought, “Lord, am I next?” But I made it and them was the only two that died during that week. Later on that week they come in with an old cow hooked to a sled—it was in the winter time and ice was all froze over, this was probably March of ’51. The lake was still froze hard. We put all the GI’s we could up on that cart and the old Korean would take off with them. And he’d go so far and the old sled was rough and the GI’s was froze just like cordwood and they’d fall off and we’d have to pick them up and lay them back up on there. And we took them off around the lake where the sandy part was and we’d bury them. And the next spring we was out on what we called the point, where our bathroom was, and you could see wild hogs out across the lake rooting where we had laid the soldiers to rest. So we told the Chinese about it and they told the Koreans, then we saw them over there digging them up but I don’t know what they did with them.

Did you ever eat any dog? Well, I have. The boy that killed the chicken, Freddie Gray, he had a black buddy in the next company and he said to me, “Kingston, let’s go see so and so.” And we did and they said, “Ya’ll sit down and eat with us.” They had a little ole table there on the floor. Freddie said, “What you got good?” And the guy said, “You know that big old black dog you’ve seen walking through the camp?” And Freddie said, “Surely you didn’t kill that dog,” But they said yes and I did eat dog—a black dog. And as far as I know it was good, but it was slick. It wasn’t like pork or chicken, but I did eat dog and the dog was better than the food we usually got. They gave us fish heads, which the fish had been frozen. And it was dried and you had to bust it apart to get to the meat in it. One time the guys were so sick and I always thought what was making them sick was these icicle radishes, which were a foot long and real red. And those people over there use human manure as fertilize. Well, they brought them radishes that was frozen and chopped them up and with that manure, dark black manure where they had dug them out of the ground, was still on the radishes and they didn’t wash them off, just barely had enough water to cook them in. And believe it or not you’d have to hold your nose to eat, but everybody did eat it. And the ones that didn’t eat it are still over there.

Then we’d get in red barley, and the Chinese would put it into a big pot and when the water got hot the weevils would come to the top and they would skim them off with a skimmer but they didn’t get them all. So, when you got your barley during the day we would say, “Well, we got our barley and meat.” And we’d laugh but we’d eat it. We didn’t pick out the weevils.

And the last year we were there they got a little better to us because they found out we was coming home. And they got in some pork and it had been froze and it had thawed up. It wasn’t the best in the world. Well, one day they made bacon and this old Chinese I asked, “When are we going home?” And he said, “When the time comes.” So, I said, “You give me a bull cart and a good-looking woman and I might just stay with ya’ll.” And that’s what they wanted you to do, they wanted you to turn against your own country. But anyway, the day they was calling out the names for us to go home, I walked up through the company and my buddy Riddle was standing up there, and my last name starts with “K” and Riddle, his started with “R” which comes a long time past K, and I said, “Did they call your name?” and he said, “yes” and I said, “Well, did they call my name?” and he said, “I don’t know.” So I said, “Well, you know what’s going to happen, don’t you? That old Chinese man is going to take me up on my offer to stay. He’s going to get me a bull cart and a good-looking woman and I’m going to have to stay here.” So Riddle says, “You think so?” And I said, “Yes, that’s what’s going to happen.”

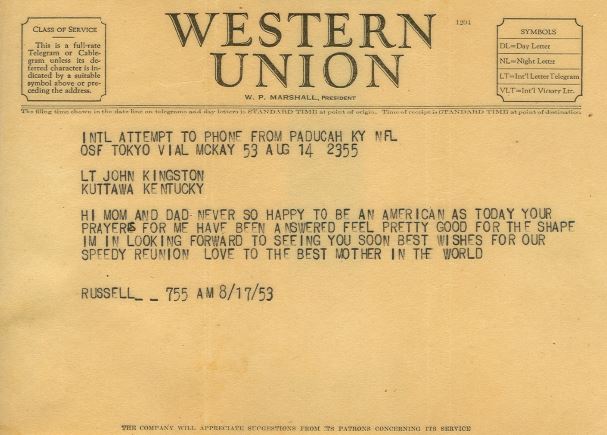

So, I stood there talking to him for a few minutes and there was an English-speaking Chinese calling out the names and he said, “That’s all the names for tonight.” And my poor old mom was sitting listening to the battery radio and she told my dad, I think it was 3 o’clock in the morning here, she said, “John, that’s all the names for tonight. They didn’t call Russell’s name.” About that time the voice came back on the PA system and said, “Here’s three more names. And they called off two names and mine was the last one for the day. And mom said, “Oh, John, they did call his name.”

When I got to California on the way home, there was a little nurse, I think with the Red Cross and she asked me if I wanted to call home and I said, “Yes.” Well, mom and dad didn’t have a phone but the restaurant I used to go to before service had one, and I will never forget the number was 9781. Well, the girl called it and handed me the phone and the guy that owned the restaurant was locking the door to close for the night. The restaurant was also a cab station and he stopped locking up and answered the phone. And it was Hart Wiseman. And I told him, I said “Hart, would you get word to my mom and dad that I will be in Louisville tomorrow afternoon at 4:20?” And he said, “Where are you now?” And I told him and he said, “Are you sure you’re going to be there at 4:20” and I said “That’s when they say the plane lands.” And he said, “I’ll tell them. And I’ll be there to pick you up.” And sure enough he and his wife, and my mother and dad and youngest brother and sister was there to pick me up at Louisville.

They picked me up and we come on down to the little town of Kuttawa. We stopped at his restaurant for a while and there was probably 200 people there. Then he brought me home and the yard was full, and the house was full and there was all my neighbors and friends come to see me when I got home. And a couple of weeks after I got home they had “Russell Kingston Day” with a parade in the little town. They gave me a brand new Browning automatic shotgun, which I still have, wouldn’t take nothing for it. They had the chamber of commerce, the mayors, bankers, judges and I rode in a big convertible. The high school band played and I’ve still got all the newspaper articles, which I wouldn’t take nothing for.

I got wounded in Korea, so I got two Purple Hearts for being wounded plus I got one for being a P.O.W. I got the combat infantry badge, the South Korean service medal, the United Nations service medal, the national defense service medal, the good conduct medal, the P.O.W. medal, and they just came out with one I’m eligible for if I want it—the Korean medal. I got ten combat battle stars, which equals two bronze stars.

In early spring in camp five, the food and water you got would give you dysentery. You couldn’t make it to the bathroom. Myself, all I had on was a field jacket and a pair of fatigues. I couldn’t make it to the bathroom in time so I crapped in my britches. I took them off and went back to my room and I hung them up on the outside of the building to dry to where I could shake them off, clean them off a bit. I went on in and that night all I had on was a field jacket with no shorts, shoes or socks. The next morning I walked out onto the little porch to get my pants to shake them out and they were gone. All I had was that field jacket, but it didn’t matter cause most of the people ran around naked in the camp anyway. Well, that shrapnel had knocked a hole in my pants. For about three weeks I went around in just a field jacket and I was standing there one day when this young soldier came by and he had on fatigue pants and he probably wasn’t much over five feet tall and he had ‘em rolled up three or four times. And I noticed when he come by I saw that hole in that one leg. And I said, “Kuksa, that was his name, I said that’s a nice pair of pants you got” and he said, “Yes, they are, army issue.” And I said, “Uh huh, they are army issue all right, but they weren’t issued to you’ and he said, “Oh, yes they was, these are mine.” So I grabbed him in front where he had a string to tighten them up, and I shook him real good and I said, “Untie them pants and let’s see what’s on the inside.” And inside it said K-and my last four on my social. So I said, “You just pull these off cause these are mine.” And he said, “Kingston, what am I gonna wear?” And I opened my jacket and I was buck naked and I said, “Looka here, that’s all I’ve worn for two weeks on account of you stealing my britches.” So, I got my pants back and I left him without any. So, he went on up through the camp with nothing on but his birthday suit. When he come up through there he didn’t have no shirt on, and when he left he didn’t have no pants on neither.

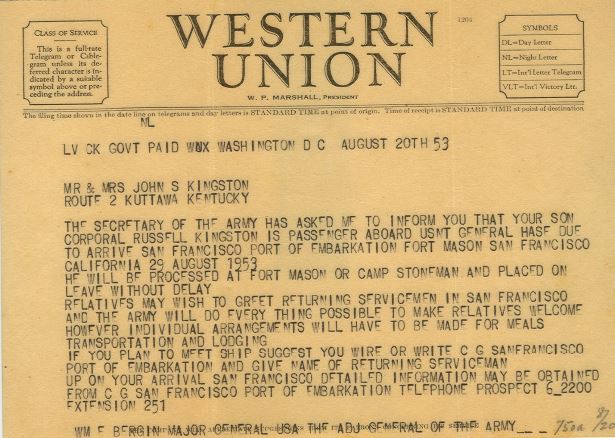

When we left the camp to come home, they put us on a boat and took us across the bay and put us on trucks. We went down through a bunch of the other P.O.W. camps and when we got down there I told some of the other guys I had been in that town, and one boy said, “Kingston, to hear you tell it you’ve been everywhere.” And I said, “I’ve been in this town. When we get around this corner look up and see if you don’t see a dam up there.” And we got around the curb and he said “You’re right.”

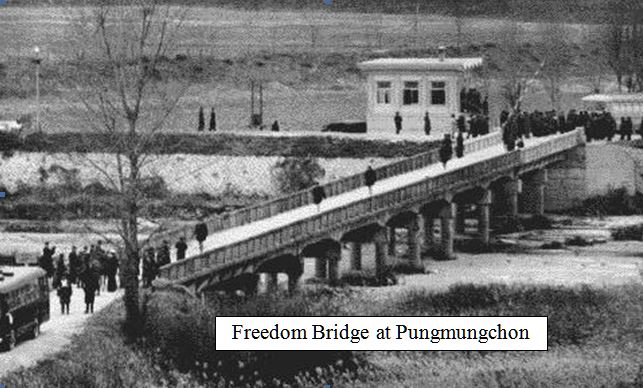

Going up north in Korea—I’m telling this in sketches—but it all works in and ties in. We went across Freedom Bridge in Panmunjom. When I come back I crossed the Freedom Bridge and most of us threw away what clothes we had on when we were liberated. All I had on was shorts. They had tents set up and welcomed us back into American hands. There was a guy there with an old spray and he stuck it into my shorts and shot some kind of powder all over you and all over your head. Then we went on into a tent and took a shower and when we came out on the other side they gave us shoes, socks, pants and shirt and a cud cap. Told us to go in the tent. I went in the tent and they wanted to know what I wanted for my first meal. I don’t remember what I told them, but I told them I wanted ice cream and while they were bringing it some aid came by and she said, “Mr. Kingston, here’s your mail.” So, they had kept the mail from coming in the camp, so she gave me my mail and I was sitting on a bunk reading my mail and someone came and said, “Here’s your food.” Well, I was more interested in my mail than I was my first meal back, so I didn’t eat any of it, and some guy came by and said, “Let’s go. It’s time to go.” So, he rushed me outside and up and bank and into a helicopter. We went from Freedom Village over Inchon into South Korea. They put us in a chain link camp with guards, to keep us from getting into the towns and we stayed there until August 16th. They put us on a ship in Inchon Bay and set sail for California two weeks later. It was either the 29th or the first day of September when I got to Kentucky. Nearly three years. And 33 months of it had been in a P.O.W. camp.

End of tape.

© Wade Kingston

Thank you for your service. Great story.

Russell, my brother-in-law, Robert Carroll was in the service in Korea at the same time, but I never heard any of his stories.

Tom, when I was growing up my Dad kept most of his experiences to himself. He would only make the most general of comments, like what the weather was like or something similar. It was only when I became an adult that he began to share.

This is a story that could be told only by someone who had been there. Thank you, Russell, for sharing, and thank you Wade for preserving these stories.

I could almost “be” there when I read this incredible story. What ingenuity and stamina you had to survive such an ordeal and live so long afterwards. I am sure that your family, including offspring, are incredibly grateful to you for lasting during these trials and tribulations.

Yes, we and the nation are generally most appreciative of whatever our soldiers were called upon to endure. We will never know the full extent of their suffering, thankfully.

We need to support these men and women effectively at each stage–from beginning of service to post-war care. They deserve no less but are not always getting this.

Well said, Helen. Though Dad may not have always gotten the care he needed or deserved, in the past 20 years that changed. He had a great friend who was a veteran of both WWII and Korea who helped him find the help he needed through the VA. What held him back so long was that he simply wasn’t aware of what was available to him, nor how to go about applying for it. I urge any veteran to visit their local VA office and investigate. Often, there is a lot available, but it isn’t automatic.

Veterans need to fight for their rights, and knowing what they are is a major first step.

I would like to talk to you further, as my grandfather was also in the same camp for the same time, and also 1st Cav from KY

Ben, Dad and I just returned from the Honor Flight Bluegrass trip to Washington, D.C. It was amazing and I heartily recommend it. I’ll reach out via your email.