Goosebumps and tingles. Goosebumps ran up both my arms and tingled around my neck as I tried to see out the bedroom window. At first, all I could make out in the dark were raindrops trickling down the panes of glass. It was summer, and the window was cracked open about an inch at the bottom. I could hear the wind moving the limbs of the big elm a few feet away. During a lightning flash I saw the top of the tree swaying to and fro.

Beside me in the feather bed, Grandma was beginning to snore. She had just finished scaring me half witless with the story of the three “Billy Goats Gruff.” I didn’t know exactly what a troll looked like, but I was fairly certain it would eat a skinny little redheaded boy alive. And so I lay awake, listening to the rain and imagining things out there in the rainy dark. Things that hid behind elm trees and grunted into the wind. Things just outside the window, with only glass between us.

It wasn’t Grandma’s fault I was too scared to sleep. It was a nightly ritual when I stayed with her that she tell me a fairy tale or two. I insisted. I began staying with Grandma when I could barely walk, and it was she who taught me to memorize poems and count on my fingers. Our lessons would last until one of us drifted off to sleep, which didn’t take long on most nights. A warm feather bed, rain on her tin roof, and almost total darkness made for terrific sleeping conditions.

Not long after I spoke my first words, Grandma began to teach me to count on my fingers. She and Grandpa went to bed “with the chickens” and often it was still daylight when we crawled onto her puffed up feather mattress. I would be tired from a day of playing on the rocky hillsides of Pea Ridge—or from accompanying Grandma on her walk to the little country store. It was a two mile round trip to Tackett’s Store, and on the return walk we would be loaded down with grocery bags.

At dusk, Grandma’s fat dominecker chickens began flapping their way up into the apple trees to roost. Grandma would pull out her tin dishpan and dip hot water from the wood stove into it. Using a cloth rubbed across homemade soap, she would wash the day’s dust off me. Then we could ease down into our cloud of feathers for a few lessons.

Eventually I could count all the way to ten on all fingers. And a couple of years later Grandpa would visit our house across from the railroad tracks in Kuttawa. He and I would sit on the front porch and I learned to count all the way to one hundred by using railroad cars as they passed. I would count the cars aloud and when I got to the caboose the count was usually around 100. “What comes after 100?” I asked Grandpa. “Well, you just start countin’ all over but put a hunnert in front of ‘em,” he told me. And I did. “A hunnert one, a hunnert two, a hunnert three…”

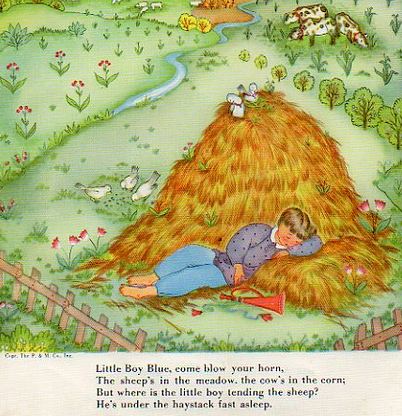

After I learned to count on my fingers, Grandma “graduated” me to reciting poems. My favorite was “Little Boy Blue.” I imagined Little Boy Blue was like me because we both lived on a farm—mine had hay fields, tobacco, corn, and sorghum. We had haystacks just like Little Boy Blue, and they were loads of fun. Big as a mountain and nearly as hard to climb, it was sheer joy to get almost to the top of a haystack only to slide backwards grasping handfuls of the fresh smelling straw. Once on top, the view seemed to go on forever, though we were only a few feet off the ground. More than once Grandpa yelled at us kids, “Ya’ll stop wallerin’ that straw down.” Then we would slide down and make hay caves out of Grandpa’s sight.

After I had learned to recite “Little Boy Blue,” Grandma was suitably proud. I was called upon to perform the poem at family gatherings. Apparently a three-year-old reciting a poem about a boy hiding under a haystack is roughly equivalent to seeing a Shakespearean play on Broadway. The applause would be enthusiastic. Adults can be impressed by youngsters who show even the slightest bit of memorization skills–something to be proud of, and no doubt I was a genius.

The nights at Grandma’s ended when I entered school. I saw her occasionally on weekends, and again during the summer. We continued the lessons until I could repeat all the poems Grandma carried in her head, as well as all the fairy tales she knew by heart. To this day I can recall perfectly Grandma saying, “Not by the hair of my chinny, chin, chin.”

She left me that—the love and patience of a grandmother teaching her grandchild to count, recite poems, and tell stories. There’s a lesson in there about the impact we can have on little children. They learn, they love–and oh how they remember.

© Wade Kingston